1

Acknowledgments

This research report originates with the work of the non-profit Reconciliation Kenora, which was founded in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Gifted the name Azhe-mino-gahbewewin (“stepping back to go forward in a good way”) by the late Anishinaabe Elder Clifford Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum), the organization’s mandate has been to promote education, support healing, and strengthen Indigenous-settler relationships in the Kenora area.

In 2018, Reconciliation Kenora / Azhe-mino-gahbewewin co-founders Janine Seymour (Wauzhushk Onigum) and Elaine Bright (settler) invited me, Jeff Denis (a settler Canadian sociologist based at McMaster University), to speak at their Annual General Meeting (AGM) and to partner on a research project about what reconciliation looks like—or could look like—in the Kenora area. Although I led the research process and wrote this report, none of it would have been possible without the support and contributions of dozens of people.

The project was inspired by both Clifford Skead and the late Anishinaabe Elder Nancy Morrison (Onigaming) who spoke at the 2018 AGM and whose words and actions embodied reconciliation. Although Clifford and Nancy passed away before the project began, an Elders Circle provided wise guidance throughout. Members included the late Stephen Kejick (Shoal Lake 39) and Jeanette Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum) as ceremonial Knowledge Keepers, as well as the late Sally Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum), Kathleen Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum), Daryl Redsky (Shoal Lake 40), Tommy Keesick (Grassy Narrows), Mary Alice Smith (settler/Omashkiigoo-James Bay Cree), Robert Greene (Shoal Lake 39), Sherry Copenace (Onigaming), Howard Copenace (Whitefish Bay), E.W. Stach (settler), and Cuyler Cotton (settler). The Elders Circle offered direction on matters ranging from interview questions to fieldwork challenges (including how to adapt during the COVID-19 pandemic), the Booshkegiin Kenora public gathering, and the content and format of this report.

I am also thankful to the research participants who generously shared their time, knowledge, and insights. Several Kenora-area residents toured me around, showing me local sites and explaining their significance, including Tommy Keesick (Anicinabe Park), Cuyler Cotton (Tunnel Island), Daryl Redsky (Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School original site), and Jeanette Skead (St. Mary’s Indian Residential School site, Wauzhushk Onigum Fall Harvest). Tracy Lindstrom (Beaver Brae Secondary School) helped coordinate the youth sharing circle and John Wapioke (Shoal Lake 39) filmed it.

Local community coordinator Sarah Beckman, appointed by the Reconciliation Kenora Board, helped bring together the initial Elders Circle, coordinate the youth sharing circle, and arrange several interviews.

McMaster University student research assistants transcribed interviews (Kerry Bailey, Daniah Kolur, Konrad Kucheran, Nick Martino), assisted with promotional materials (Konrad), and helped edit, design, and format this website/report (Daniah).

The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada provided funding in the form of an Insight Development Grant.

Lastly, I am deeply grateful to the Anishinaabeg of Treaty #3 for welcoming me to their lands and allowing me to do this work. I hope this report will benefit the community and generations to come.

Dr. Jeffrey Denis

Associate Professor, Sociology

McMaster University

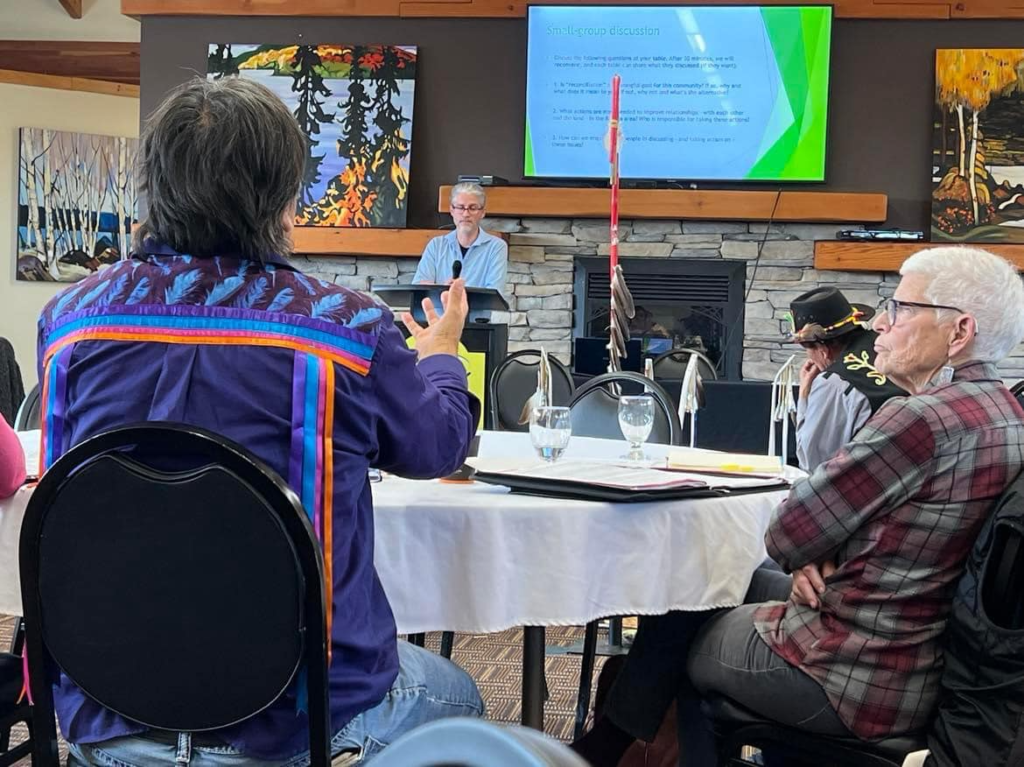

Figure 1: Reconciliation Kenora / Azhe-mino-gahbwewin Elders Circle meeting, June 11, 2025. Left to right front row: Cuyler Cotton, Howard Copenace, Robert Greene, Jeffrey Denis, Jeanette Skead, Sherry Copenace, Kathleen Skead. Back row on computer screen: Mary Alice Smith. [Photo by Daniah Kolur]

1

Executive Summary

What does reconciliation mean in Kenora today? This report shares findings from the Azhe-mino-gahbewewin / Reconciliation Kenora research project, a community-driven effort to understand what reconciliation means in the Kenora area, identify local priorities and barriers, and chart possible paths forward. The project was launched in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action and was co-designed by the non-profit Reconciliation Kenora and Dr. Jeffrey Denis, a settler sociologist at McMaster University. It was guided throughout by an Elders Circle and grounded in local knowledge and community relationships.

The project began in 2019 with a youth sharing circle involving 11 Anishinaabe, Métis, and non-Indigenous participants, but was soon interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team adapted by conducting 47 in-depth Zoom interviews with Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents, including Elders, Knowledge Keepers, activists, and community leaders. Of these, 17 were Anishinaabe from local First Nations, 5 were Métis, 5 were Indigenous people who had moved to Kenora from other regions, and 20 were settlers. Additional insights came from ongoing engagement with the Elders Circle, participation in community events, and a 2023 public gathering, “Booshkegiin Kenora.”

Findings show that reconciliation remains a powerful but contested concept. Many participants described it as a long-term, relational process grounded in education, healing, respect, and restoring balance—between peoples and with the land. Others emphasized the Anishinaabemowin term Azhe-mino-gahbewewin, meaning “stepping back to go forward in a good way,” as a more locally rooted and culturally resonant framework. Some Indigenous participants questioned or rejected the notion of reconciliation altogether, stressing that respectful, equitable relationships never existed to begin with, and calling instead for decolonization, resurgence, and Indigenous self-determination.

Participants agreed that Indigenous-settler relationships in Kenora have long been marked by inequality, racism, and violence. While some progress has been made—such as increased Indigenous cultural visibility, growing representation, and more cross-cultural interaction—many barriers remain entrenched. These include systemic racism, colonial laws and policies, settler myths and ignorance, tokenism, and persistent power imbalances across institutions. Indigenous Peoples in the region continue to face disproportionate rates of poverty, houselessness, and mental health challenges. These realities are deeply rooted in colonial trauma.

Yet, Indigenous communities are also experiencing resurgence and renewal. Despite its challenges, Kenora is home to a long history of anticolonial resistance and Indigenous-settler bridge-building—from Canada’s first civil rights march in 1965 to the Anicinabe Park occupation in 1974, and numerous grassroots reconciliation efforts since. These include educational initiatives, community celebrations, commemoration events, land-based healing and cultural camps, housing and health supports, Indigenous-led advocacy, and cross-cultural partnerships.

Going forward, participants highlighted the importance of building trust, listening across differences, confronting uncomfortable truths, and taking concrete, collective action. Many said that while reconciliation is everyone’s responsibility, the primary burden lies with settlers and settler institutions, given how they have benefited from colonization.

Key recommendations include investing in Indigenous-led programs, services, and cultural revitalization initiatives; fostering youth leadership and intergenerational dialogues; improving educational curricula; building more affordable and supportive housing; eliminating systemic barriers in healthcare and justice; creating more welcoming, inclusive spaces; fulfilling treaty obligations; returning land to Anishinaabe stewardship; respecting Anishinaabe law and jurisdiction; and developing mechanisms to monitor progress. Above all, the report underscores the need for reconciliation efforts to be rooted in local relationships, guided by Indigenous voices, and sustained through meaningful, structural change—not just symbolic gestures.

Next steps should include further research to better understand the needs and experiences of marginalized residents, particularly those living on the streets, and to identify ways to engage settlers who currently see reconciliation as irrelevant to them. The report recommends a collaborative process for using these findings to help shape strategic action plans to advance reconciliation in the Kenora region. It also calls on local Indigenous and settler leadership—including Grand Council Treaty #3 and the City of Kenora, both of which have expressed commitments to relationship-building—to help guide the implementation of these recommendations. The path forward requires courage, honesty, and collaboration. It also requires developing more equitable and sustainable relationships with each other and the land. This report invites everyone in the Kenora region to play a role in that work.

1

Background

Research Project Origins, Team, and Goals

The goals of this research project were to document what reconciliation means to Kenora-area residents, identify barriers to reconciliation, and highlight actions that have been taken—and should be taken—to advance reconciliation in Treaty #3. The idea for the project originated in 2018 when the non-profit organization Reconciliation Kenora / Azhe-mino-gahbewewin invited Dr. Jeffrey Denis—a settler Canadian and Associate Professor of Sociology at McMaster University—to speak at its annual general meeting (AGM).

Reconciliation Kenora was founded in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s 2015 final report by two Kenora-based lawyers, Janine Seymour and Elaine Bright. Ms. Seymour, an Anishinaabekwe from Wauzhushk Onigum Nation, had worked for the TRC documenting the stories of Indian Residential School (IRS) survivors. Ms. Bright, a settler who had moved from Toronto to Kenora, worked with survivors seeking compensation under the 2006 IRS settlement agreement. Inspired by the TRC Calls to Action (2015) and by their own experiences in Treaty #3, they created Reconciliation Kenora with a mandate to improve local relationships and promote education and healing. They established a board of directors with Anishinaabe, Métis, and non-Indigenous members, and were guided by ceremonial Elders Jeanette Skead and her late husband Clifford Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum). Early initiatives included hosting a reconciliation powwow, workshops on colonialism, land-based learning and reconciliation camps, and the creation of a community medicine garden.

At the 2018 AGM, Dr. Denis presented findings from his earlier research on Indigenous-settler relations in the Fort Frances area (published in 2020 as Canada at a Crossroads). This research documented “boundaries” and “bridges” between Indigenous and settler communities and examined why anti-Indigenous racism persisted even amid widespread cross-group relationships. His findings resonated with the audience, which included Reconciliation Kenora board members, Kenora city councillors, the late Anishinaabe Elder Nancy Morrison (Onigaming), and Grand Chief of Treaty #3 Francis Kavanaugh (Naotkamegwanning).

After the meeting, Reconciliation Kenora board members approached Dr. Denis about applying for research funding to study what reconciliation might look like in Kenora. The rationale was to clarify local Indigenous and non-Indigenous visions for reconciliation, identify priorities for action, and find ways to engage more settlers in the process. It was thought that answering such questions through research could help inform a strategic plan to act on the local vision(s) and develop concrete measures of success. From an academic perspective, Dr. Denis was also interested in how local histories and social contexts shape the meaning(s) of reconciliation and the possibilities for action.

Dr. Denis then applied for and received a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Development Grant (SSHRC IDG) to conduct the research. The grant proposal, including the research questions and methods, was developed collaboratively with Reconciliation Kenora board members, including Elaine Bright (co-chair), Kathleen Skead (co-chair), Jeanette Skead, Daryl Redsky, Sarah Beckman, E.W. Stach, Delores Kelly, Lloyd Comber, Martin Camire, Rory McMillan, Will Landon, Jake Boutwell, Candice Holmstrom, and Tracy Lindstrom. Upon receiving the grant, the board appointed a local community coordinator, Sarah Beckman, to help arrange interviews, sharing circles, and logistics. McMaster University students Kerry Bailey, Daniah Kolur, Konrad Kucheran, and Nick Martino were hired as research assistants to transcribe interviews and support other tasks.

In consultation with the board, an Elders Advisory Circle was also formed to provide guidance throughout the project. The initial Circle included ceremonial Knowledge Keepers Jeanette Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum) and Stephen Kejick (Shoal Lake 39), as well as Sally Skead (Wauzhushk Onigum), Daryl Redsky (Shoal Lake 40), Tommy Keesick (Grassy Narrows), and Mary Alice Smith (settler/Omashkiigoo-James Bay Cree). After the passing of Elders Stephen Kejick and Sally Skead, and as the project adapted to COVID-19 pandemic conditions, additional Elders were invited, including Robert Greene (Shoal Lake 39), Sherry Copenace (Onigaming), and Howard Copenace (Naotkamegwanning). Upon the Elders’ advice, a few experienced and trusted settler residents—E.W. Stach and Cuyler Cotton—were also included in the Circle.

In short, the overall aim of this project was to conduct research that could inform an action plan to advance reconciliation locally. To this end, we asked participants what reconciliation means to them, what barriers they see, and what actions have been taken or should be taken to improve relationships in the Kenora area. We also inquired about their perceptions of how Indigenous-settler relationships had changed (or not) over time, reconciliation initiatives in which they had been involved, recent local incidents related to racism or reconciliation, and their hopes and visions for the future.

Research Process: Data, Methods, and Challenges

As a first step, Dr. Denis met with the Elders Circle in 2019 to seek advice on the research design. Following local cultural protocols, Elders were offered tobacco and honoraria. The plan was to hold separate sharing circles with Elders, youth, and people living on the streets—people whose voices are not always heard. In December 2019, one sharing circle was held at Beaver Brae Secondary School with 11 Anishinaabe, Métis, and non-Indigenous youth. The circle was co-facilitated by Daryl Redsky and attended by Elders Jeanette Skead and Tommy Keesick. Rich conversations unfolded over roughly three hours, and the session was video recorded. Student participants received lunch and gift cards in appreciation for their time and contributions.

Although additional sharing circles were scheduled for spring 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic forced the project to pause for more than a year. As the pandemic dragged on, and as several Elders we had planned to interview passed away, we pivoted to Zoom interviews with participants who were comfortable using the technology and speaking one-on-one. In total, Dr. Denis conducted 47 in-depth interviews, primarily with Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and leaders in local Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Of these, 17 were Anishinaabe from local First Nations, 5 were Métis, 5 were Indigenous people who had moved to Kenora from other regions, and 20 were settlers (7 of whom were born and raised in Kenora). Interviews ranged in length from approximately one hour to more than three hours and were transcribed verbatim.

Since 2022, Dr. Denis returned to Kenora multiple times to meet with the Elders Circle and attend community events, including a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (Orange Shirt Day) walk, the Wauzhushk Onigum Fall Harvest, and the 50th anniversary of the Anicinabe Park occupation. He also met informally with many research participants and spent time at Tunnel Island, the Kenora Fellowship Centre, The Muse, Shoal Lake 40 First Nation’s Museum of Canadian Human Rights Violations, and local IRS memorial sites (St. Mary’s and Cecilia Jeffrey).

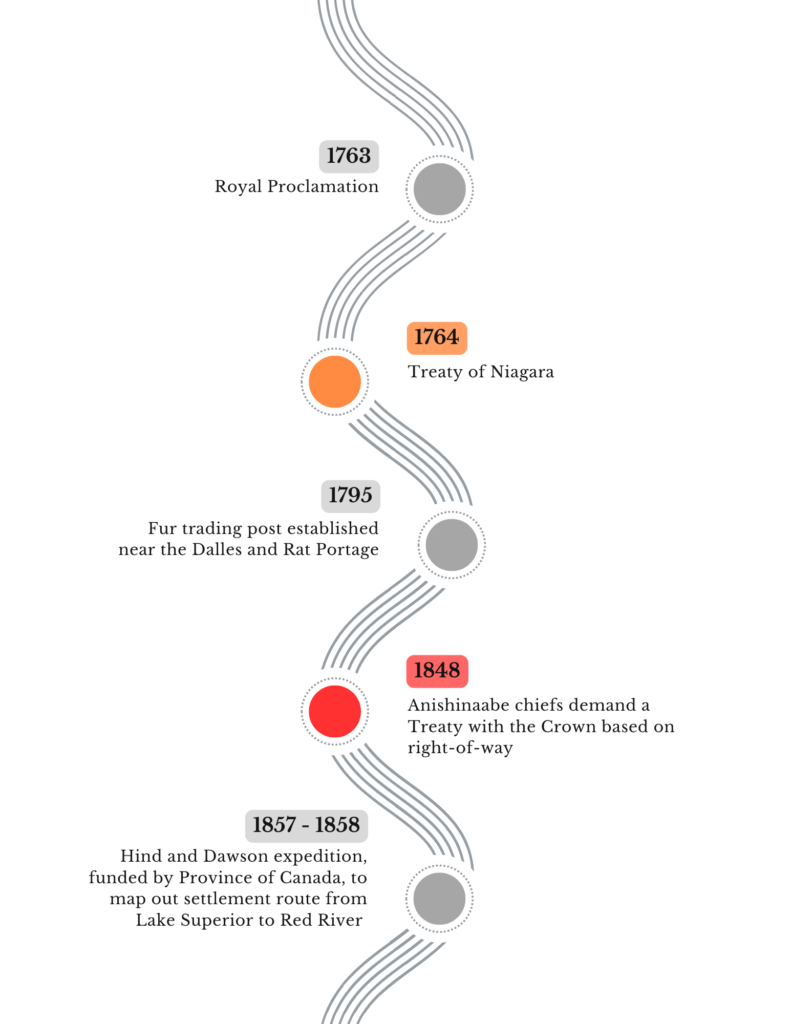

In October 2023, a public gathering known as “Booshkegiin Kenora” (“It’s Up to You”) was held in partnership with Kenora Moving Forward, a grassroots coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents working with people on the streets to improve their safety and sense of belonging (KMF Coalition, 2023). At that video-recorded event, Dr. Denis presented preliminary findings from the Reconciliation Kenora research project and invited further discussion. Feedback from that gathering has been incorporated into this report.

A further challenge that must be noted here is that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Reconciliation Kenora board stopped meeting and, at least temporarily, ceased functioning as an organization. Nevertheless, Dr. Denis continued to consult with the Elders Circle and, with its guidance, completed the research in hopes that it would still benefit the wider community. The stories and insights shared in interviews and sharing circles were extremely rich and there is much to learn from the project that may inform future research, policies, practices, and strategic action plans.

It should also be noted that, in the sections that follow, some interview and sharing circle quotations are attributed to individuals who gave permission for their names to be used. Others remain unnamed because participants preferred anonymity or did not respond to requests regarding their preferences.

Reconciliation in Context: Key Terms and Local History

Before sharing the research findings, it is important to contextualize this study. This section does so in two ways: (1) by summarizing key debates about reconciliation in the academic literature, and (2) by outlining the local history of Indigenous-settler relations in the Kenora area.

Debates about Reconciliation

Across Canada, dozens of organizations, many of them Indigenous led, are working toward reconciliation (Davis et al., 2017). These include national groups, such as Reconciliation Canada and the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, as well as smaller community-based groups like Reconciliation Kenora / Azhe-mino-gahbewewin, the community partner on this project. At the same time, ongoing violence and injustices against Indigenous Peoples—from the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (National Inquiry into MMIWG, 2019) to federal approvals of mines and pipelines without Indigenous consent—have led some Indigenous activists to declare that “reconciliation is dead” (Ballingall, 2020). This sentiment was reiterated after 215 potential unmarked graves of children were uncovered at the former IRS site in Kamloops, B.C., in 2021 (Dickson & Watson, 2021).

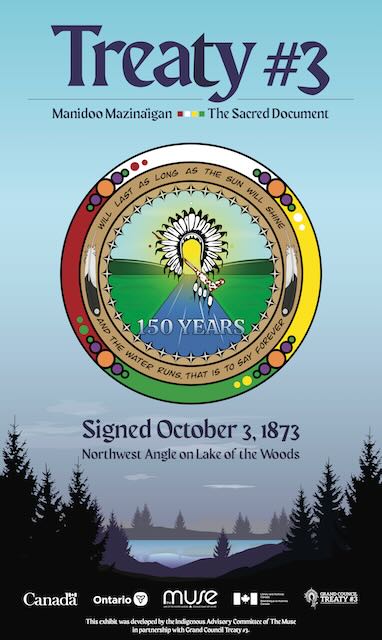

Reconciliation is a widely used and much contested term in the academic literature (e.g., Borrows & Tully, 2018; Brant Castellano, Archibald, & DeGagné, 2008; Clark, De Costa, & Maddison, 2016; Craft & Regan, 2020; Daigle, 2019; Denis & Beckman, 2022; Freeman, 2014; Henderson & Wakeham, 2013; Mathur, Dewar, & DeGagné, 2011; Paquette, 2020; Simpson, 2017; Snelgrove, 2021; Stark, Craft, & Aikau, 2023; Whyte, 2018; Younging, Dewar, & DeGagné, 2009). While dictionary definitions tend to emphasize the idea of restoring friendly relations after a conflict, the TRC (2015) noted in its final report that “friendship” never characterized Indigenous-settler relations in some regions. Nonetheless, Treaty #3 was negotiated in 1873 between the Anishinaabe and the Crown in what is now called Northwestern Ontario. From an Anishinaabe perspective, the treaty is a nation-to-nation agreement to share the land and resources, respect one another’s political autonomy, and support one another in times of need (Denis, 2025; Krasowski, 2019; Luby, 2010; Mainville, 2007). In this context, the TRC’s (2015: 113) notion of reconciliation as peaceful co-existence and “healthy relationships … going forward” may still resonate.

Canadian governments, churches, and some Indigenous leaders began promoting reconciliation in the late 20th century, especially after the 2008 federal apology for the IRS system. However, many Indigenous scholars and activists were critical of this focus. Given that colonial policies and practices continue to operate in Canada, they argued that reconciliation put the cart before the horse (Alfred, 2009; Corntassel & Holder, 2008; Coulthard, 2014; Simpson, 2014). In their view, reconciliation was an inappropriate—and potentially harmful—framework, especially if led by colonial governments that retained control over the process. Public apologies, they argued, risked being more performative than transformative (Daigle, 2019), offering settlers a sense of moral relief without addressing structural inequality (Alfred, 2009). They urged Indigenous Peoples to turn away from state-centred recognition politics and toward resurgence—revitalizing Indigenous governance systems, languages, family structures, and ways of life (Corntassel, 2012; Coulthard, 2014; Simpson, 2017).

The TRC (2015), meanwhile, upheld reconciliation as a worthy goal, offering 94 Calls to Action to guide its pursuit. Appointed by the federal government after the 2008 apology, the TRC spent six years investigating the history, experiences, and consequences of the IRS system. Its final report defined reconciliation as a complex, multidimensional, and multi-generational process that must involve education, healing, commemoration, cultural revitalization, respect for treaty, constitutional, and human rights, closing gaps in socioeconomic and health outcomes, and “integrating Indigenous knowledge systems, oral histories, laws, protocols, and connections to the land into the reconciliation process” (TRC, 2015: 3).

Following the release of the TRC report, polls showed that a majority of Canadians supported the principle of reconciliation (Environics, 2016). A growing body of work, much of it by Indigenous authors, offers practical tips on “ways to reconcile” (e.g., LeMay, 2025; Robertson, 2025). To date, however, few of the TRC Calls to Action have been implemented (Jewell & Mosby, 2023). Moreover, reconciliation often means different things to Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Denis and Bailey (2016) found that while many settlers who participated in TRC events endorsed most aspects of the TRC’s definition of reconciliation, they rarely recognized the centrality of land for Indigenous participants. Although many settlers may support education, healing, and relationship-building, they are less likely to call for dismantling the colonial state or advancing Indigenous land back efforts (cf. Simpson, 2016, 2017).

A Brief Overview of the Local History of Indigenous-Settler Relations

One understudied issue is how the meanings and possibilities of reconciliation depend on local context. What does reconciliation look like—or what could it look like—in Treaty #3? As Anishinaabe Elder Fred Kelly (Onigaming) writes, “If reconciliation is to be real and meaningful,” it cannot be a “generic process … imposed on [Indigenous] peoples without regard to their own traditional practices” (Kelly, 2008: 22). It must be rooted in local histories and relationships, and “embrace the inherent right of self-determination through self-government envisioned in the treaties” (23).

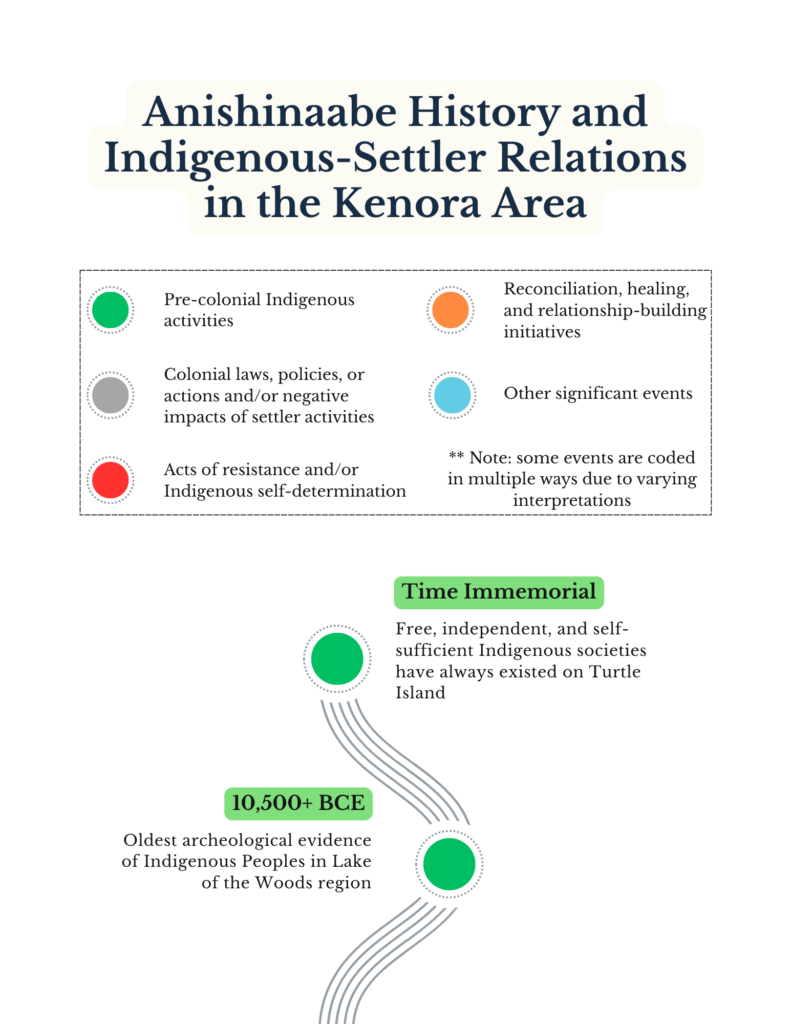

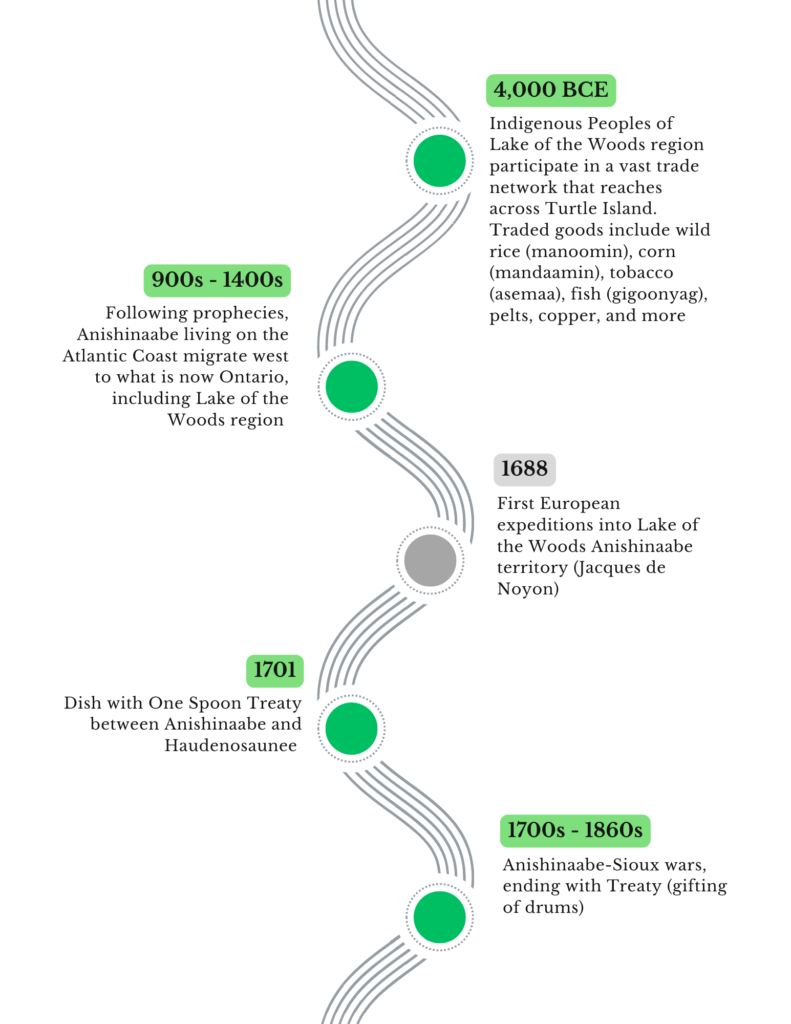

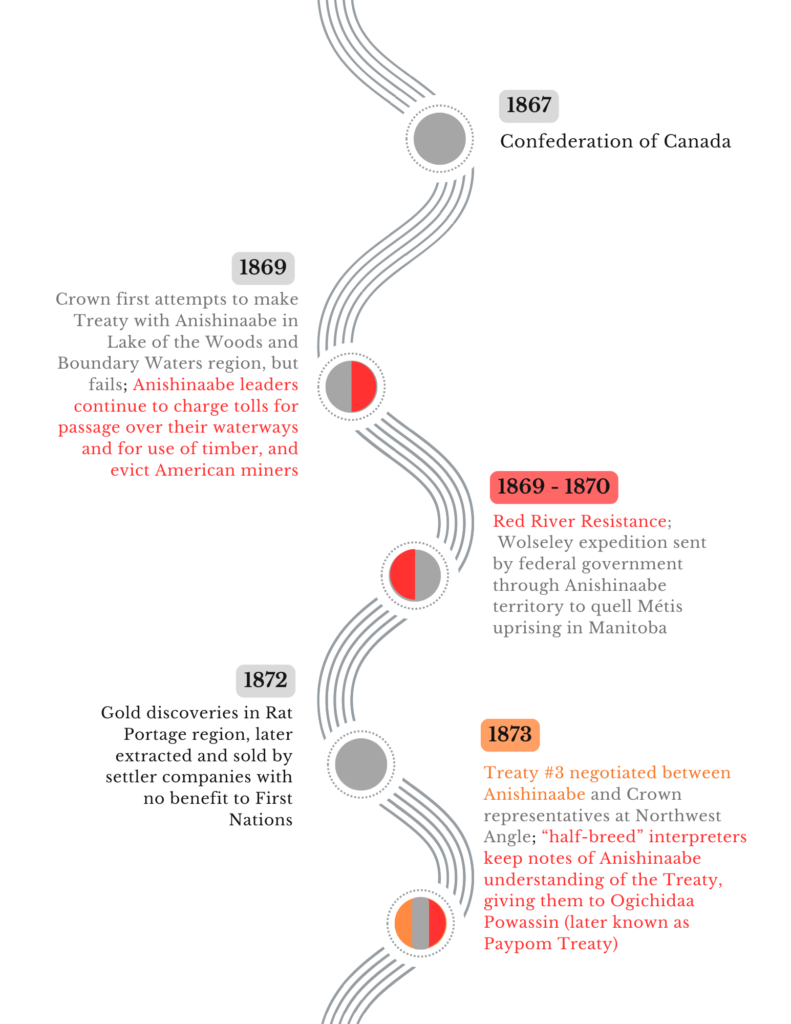

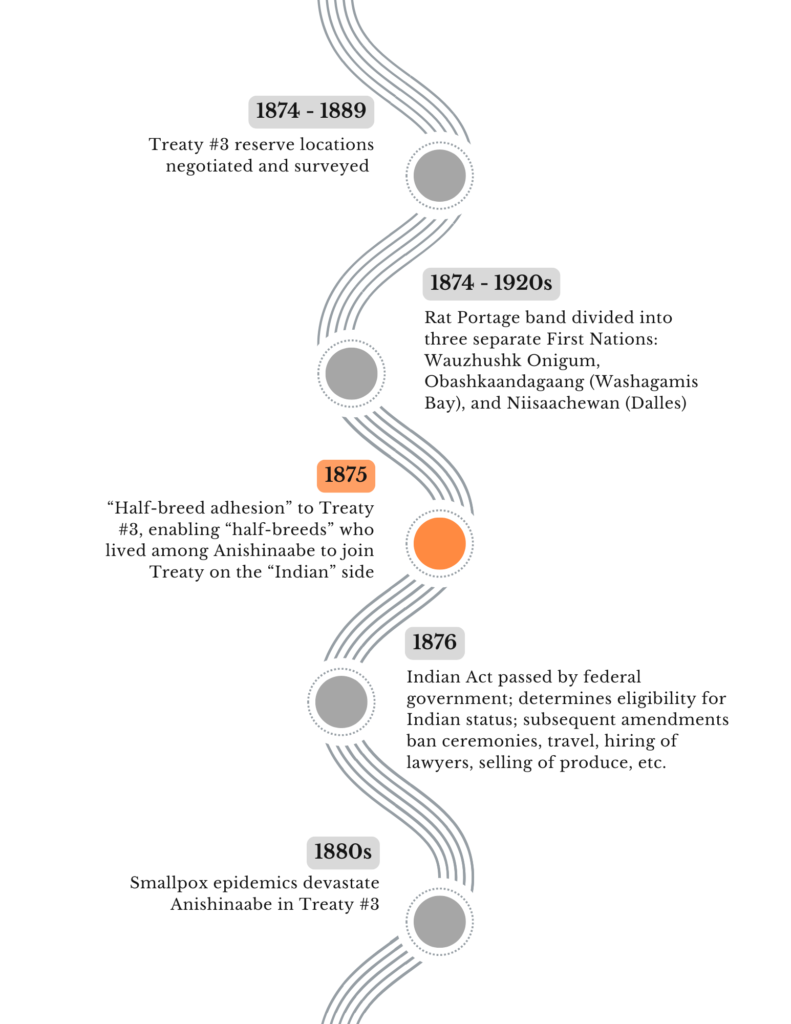

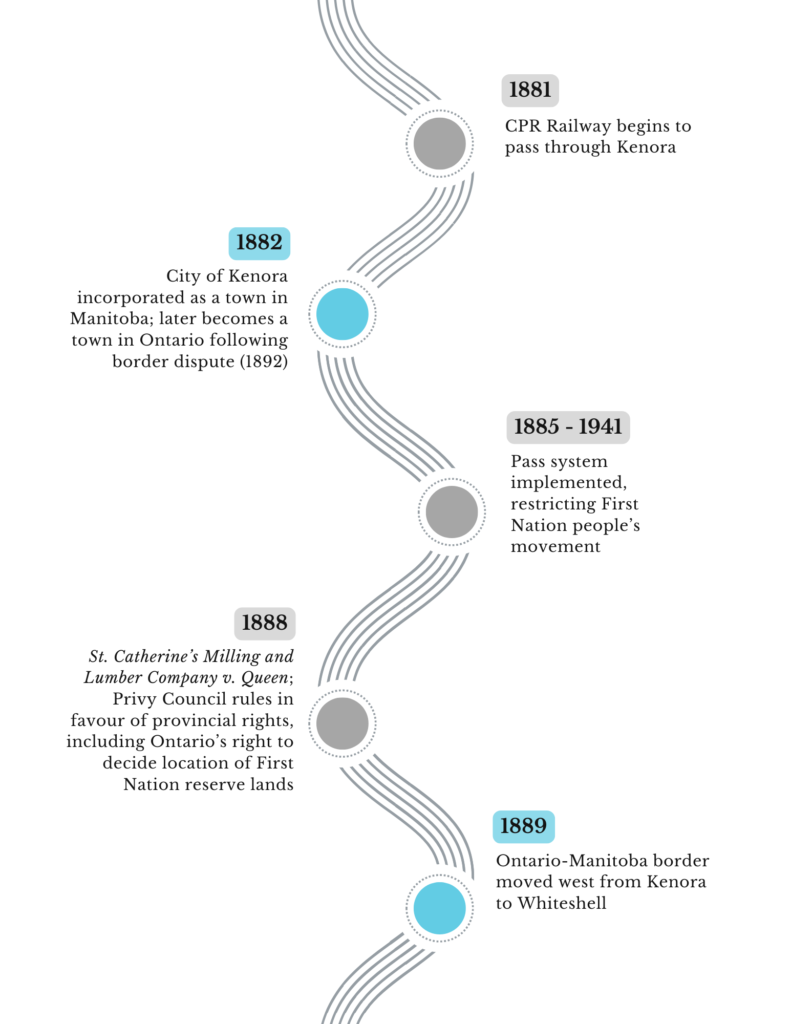

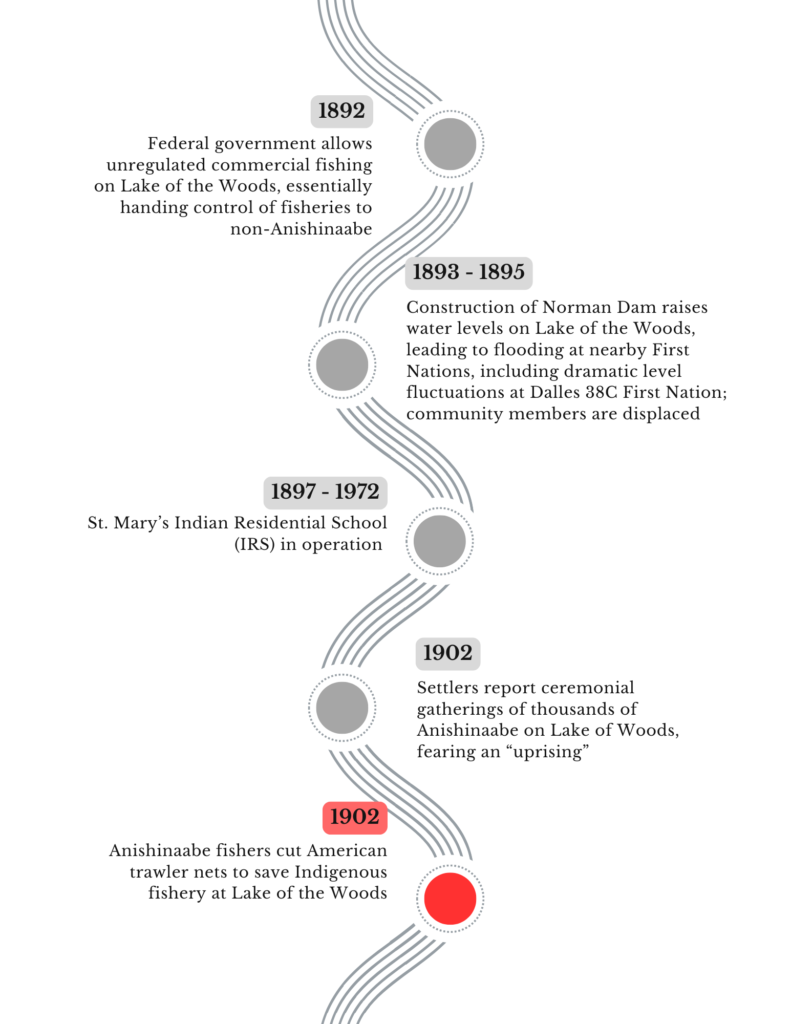

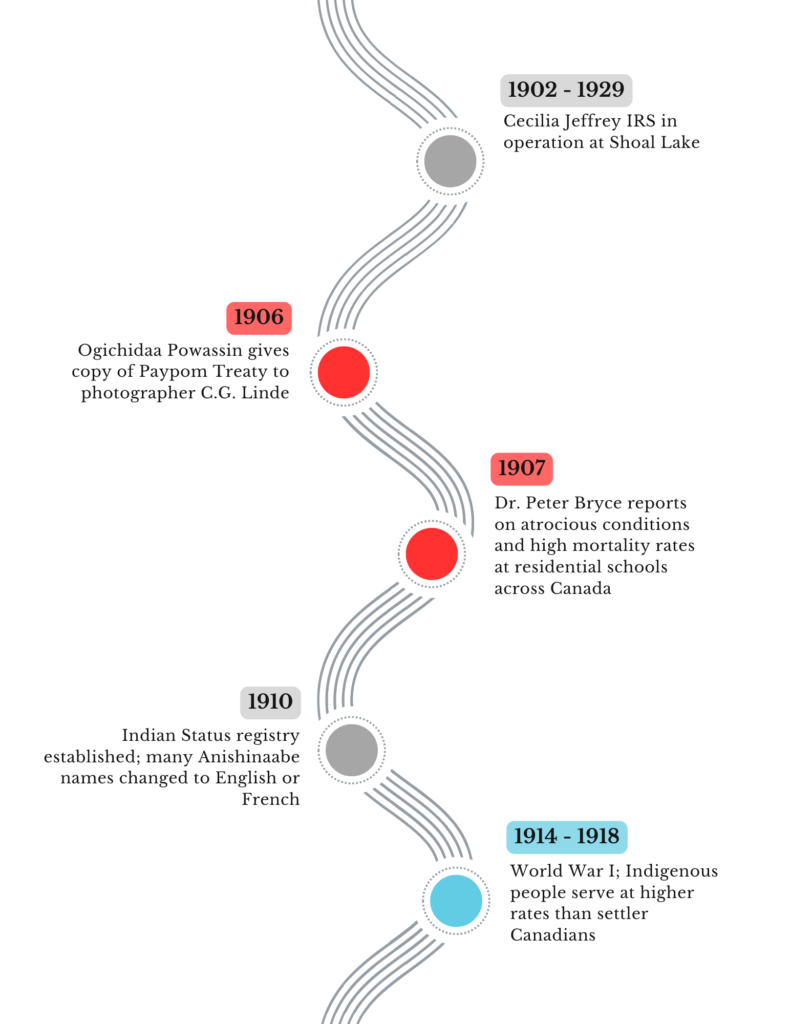

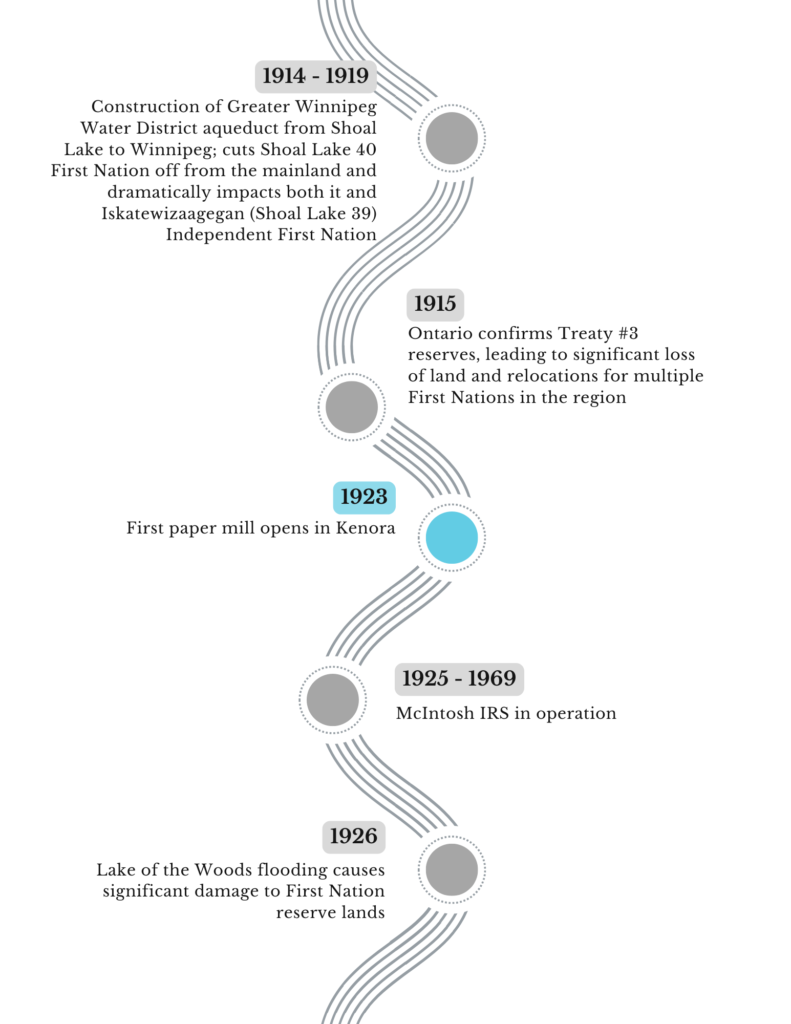

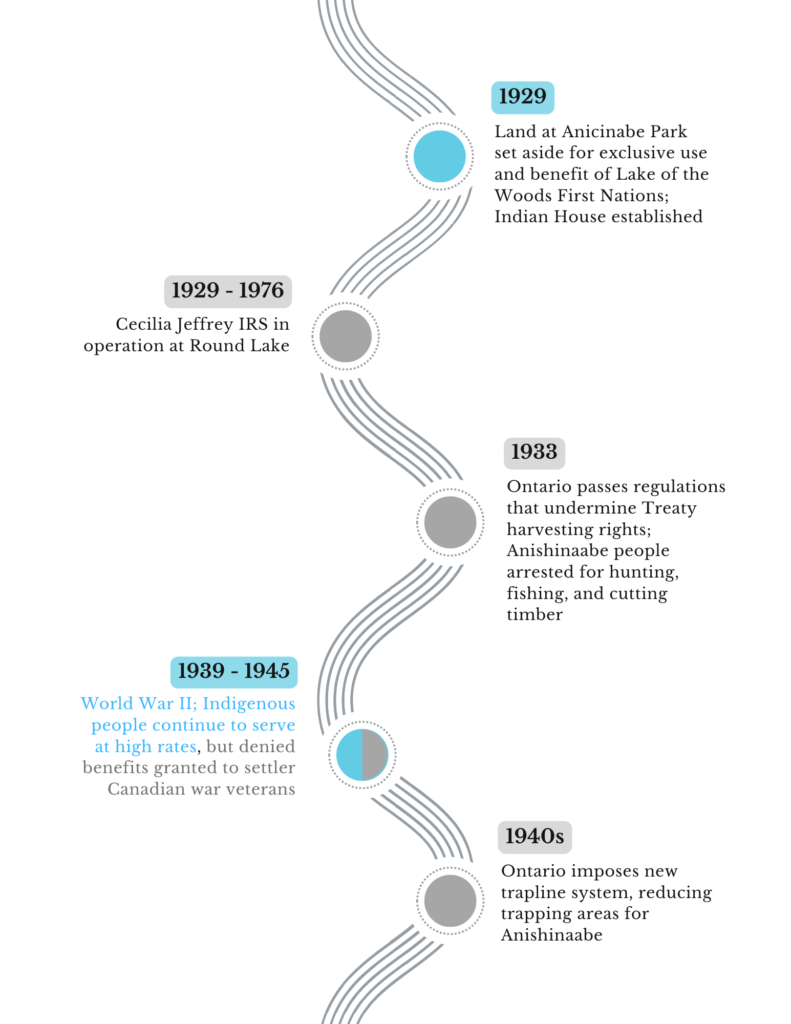

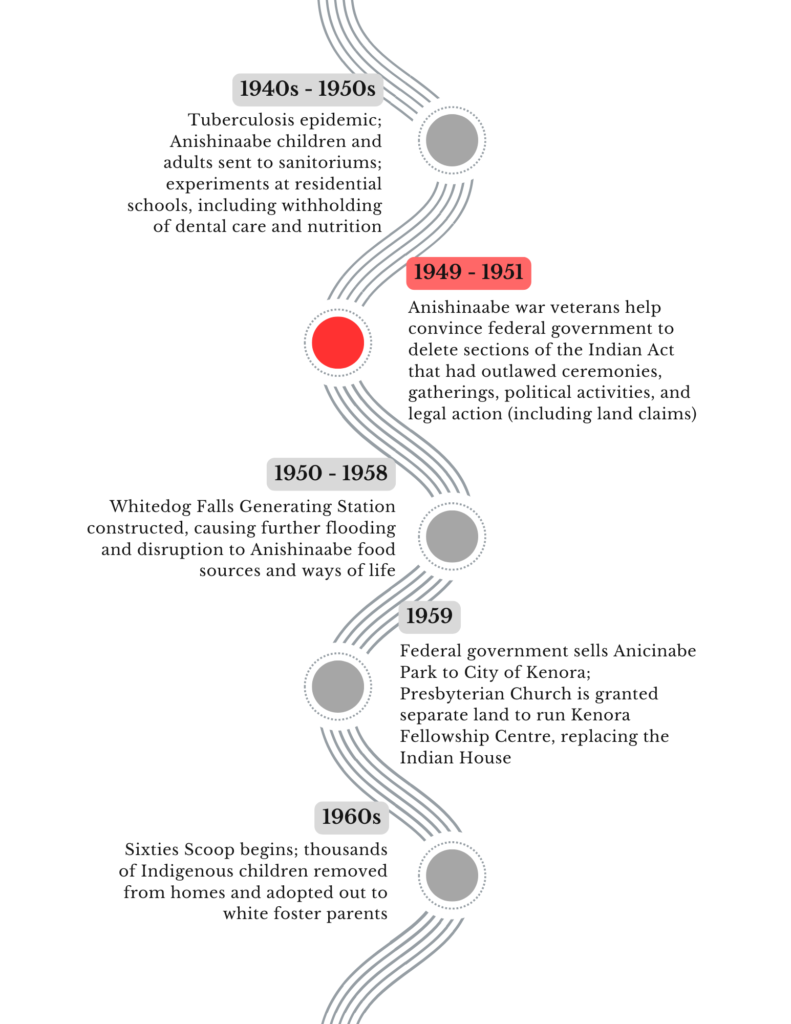

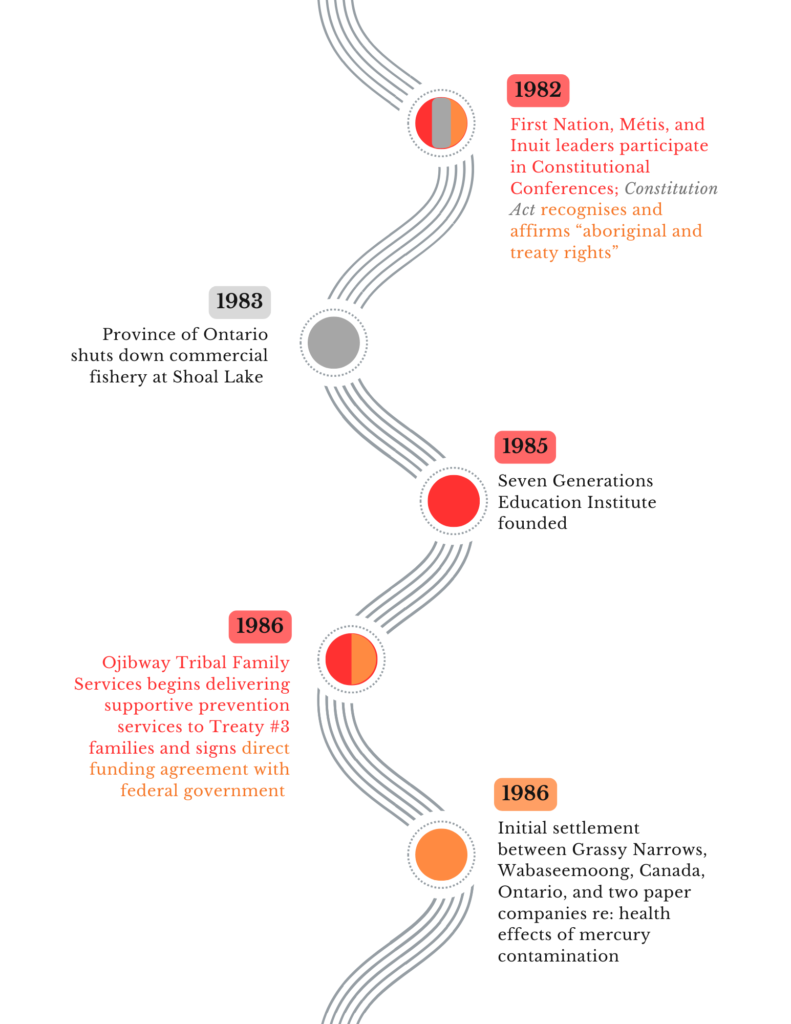

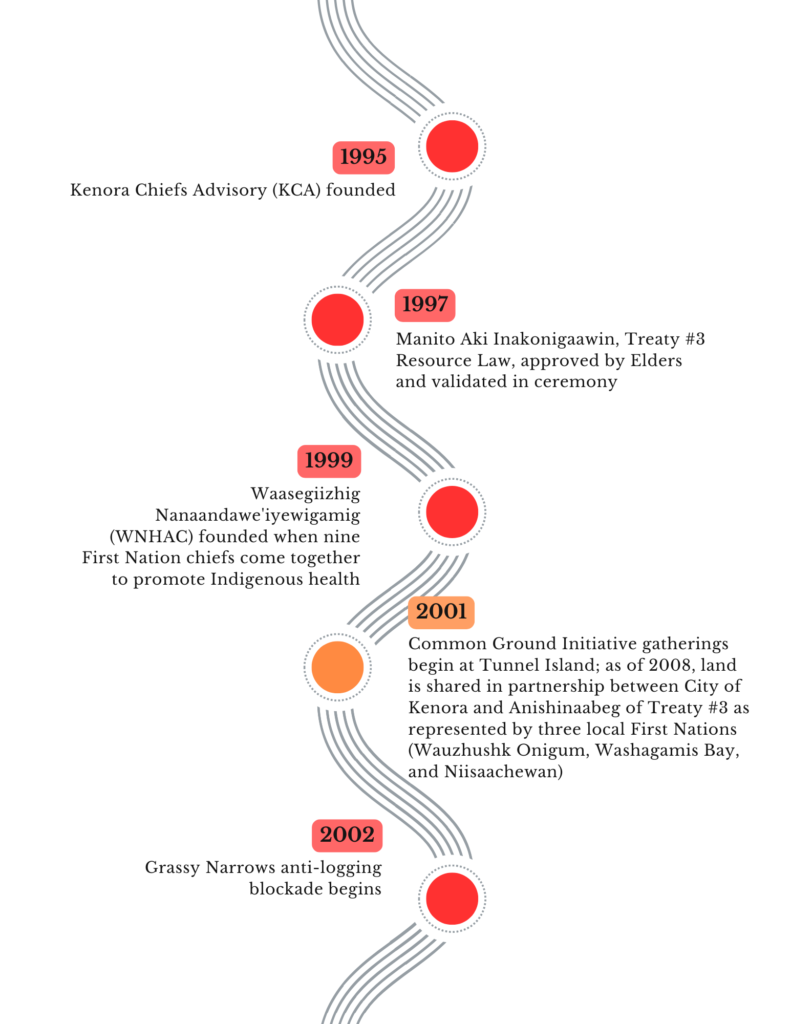

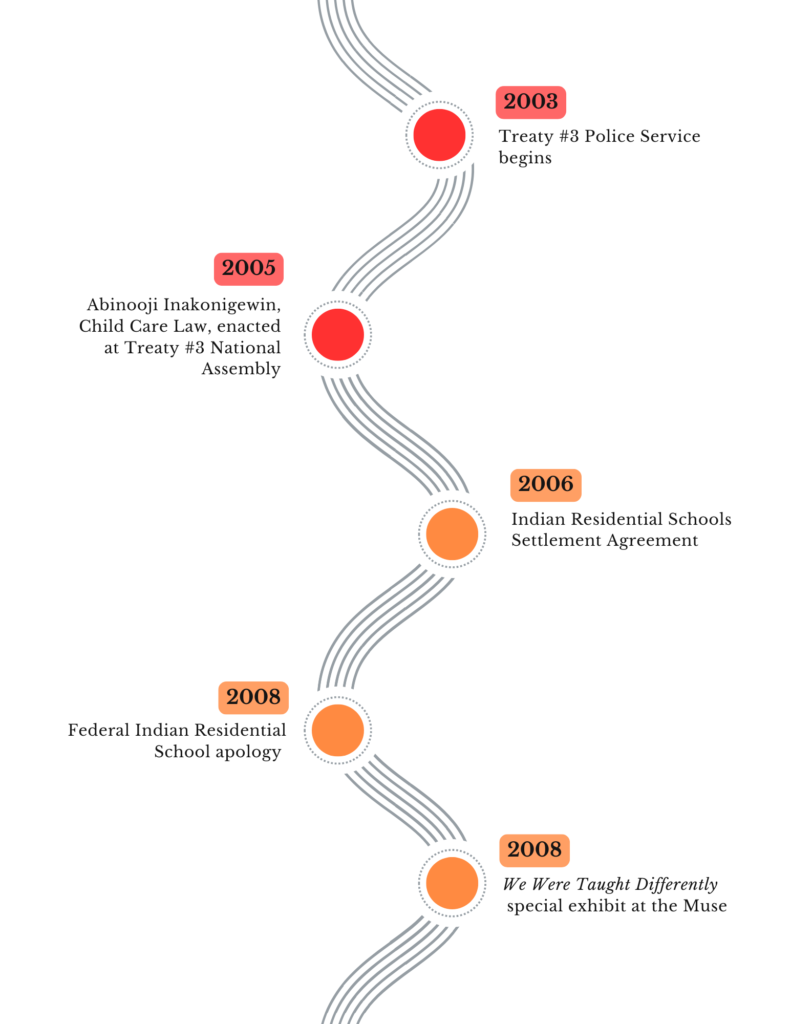

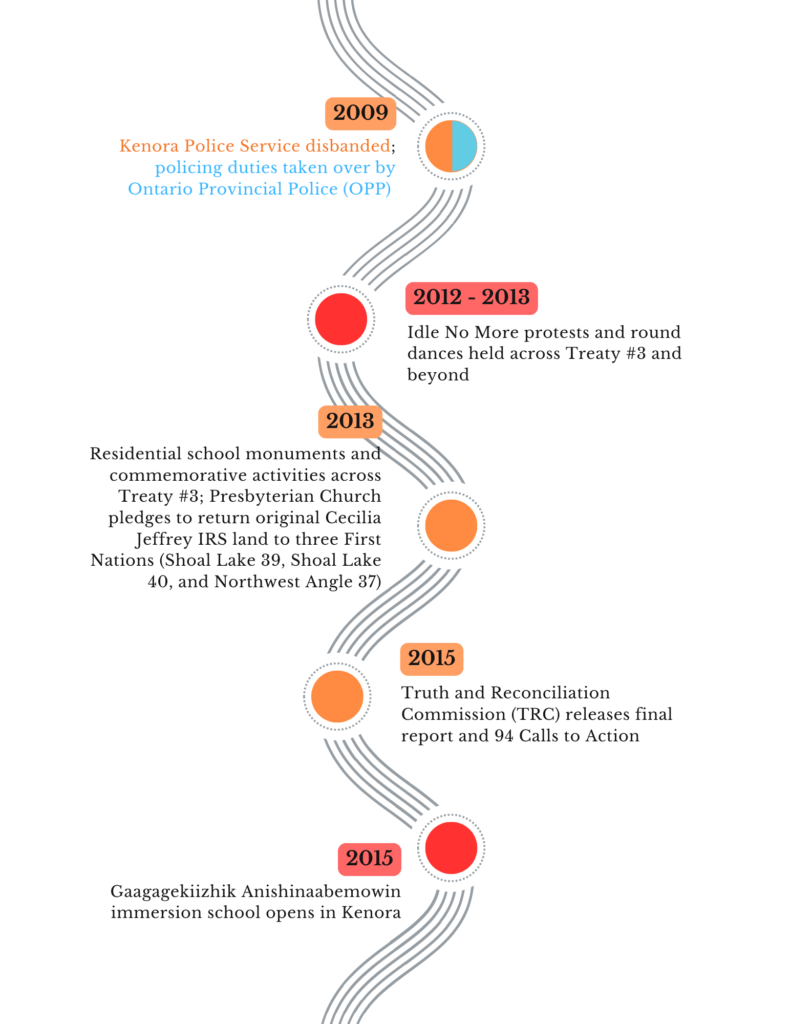

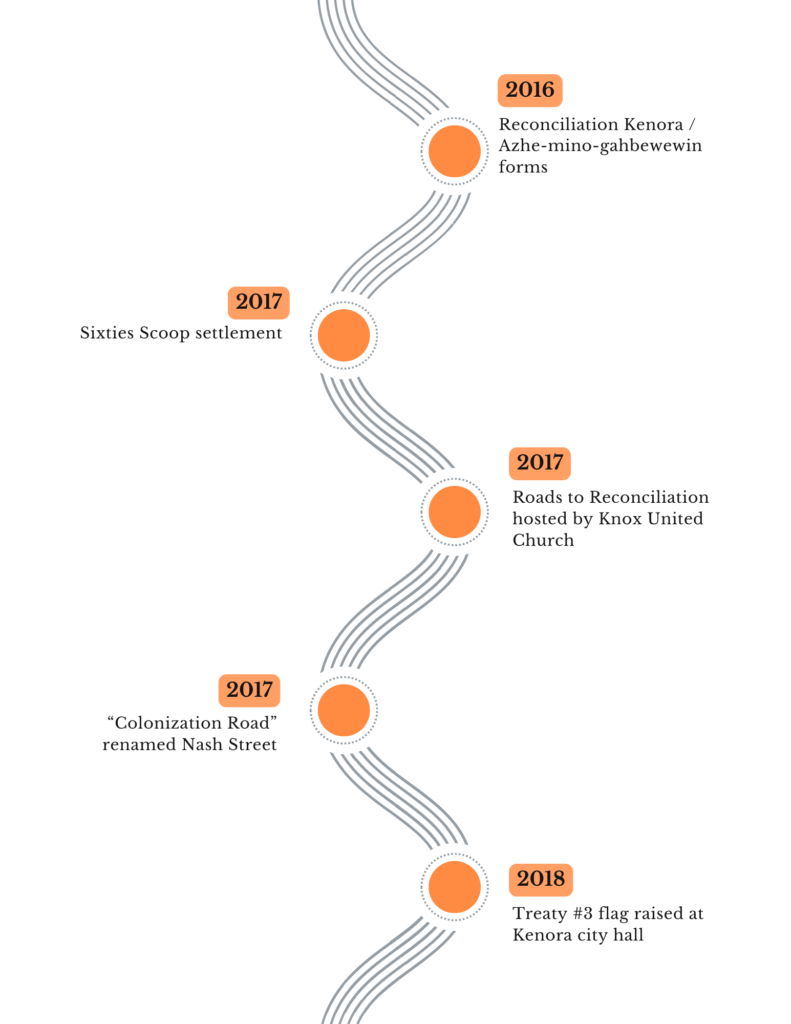

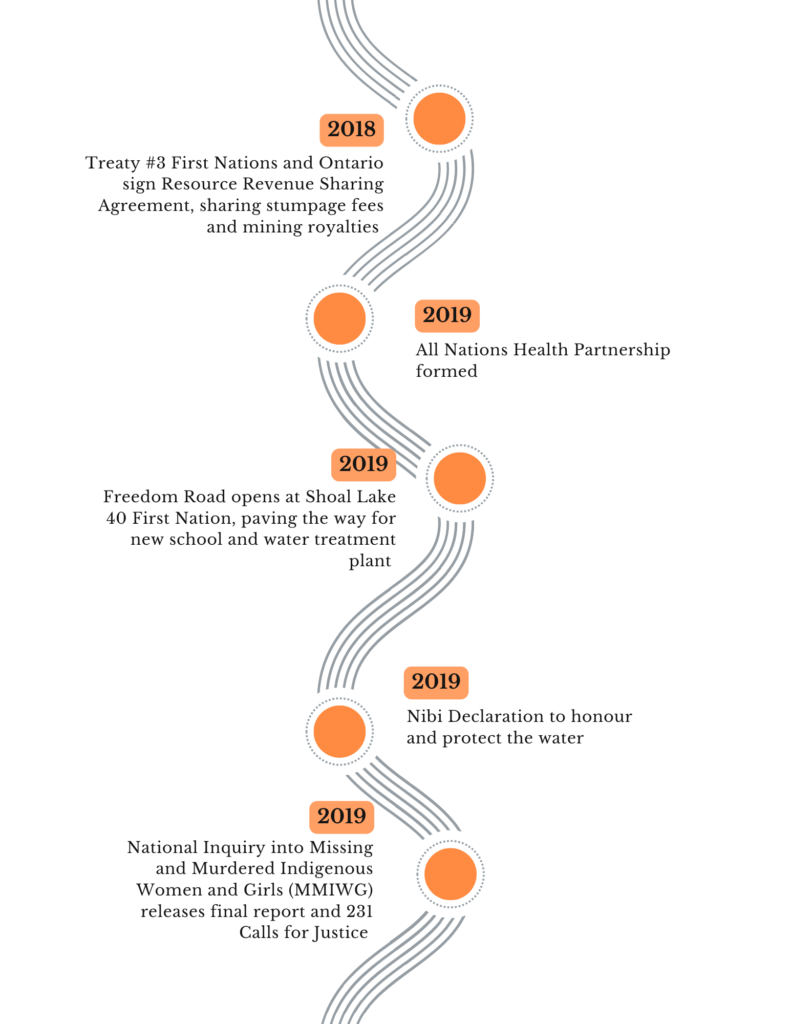

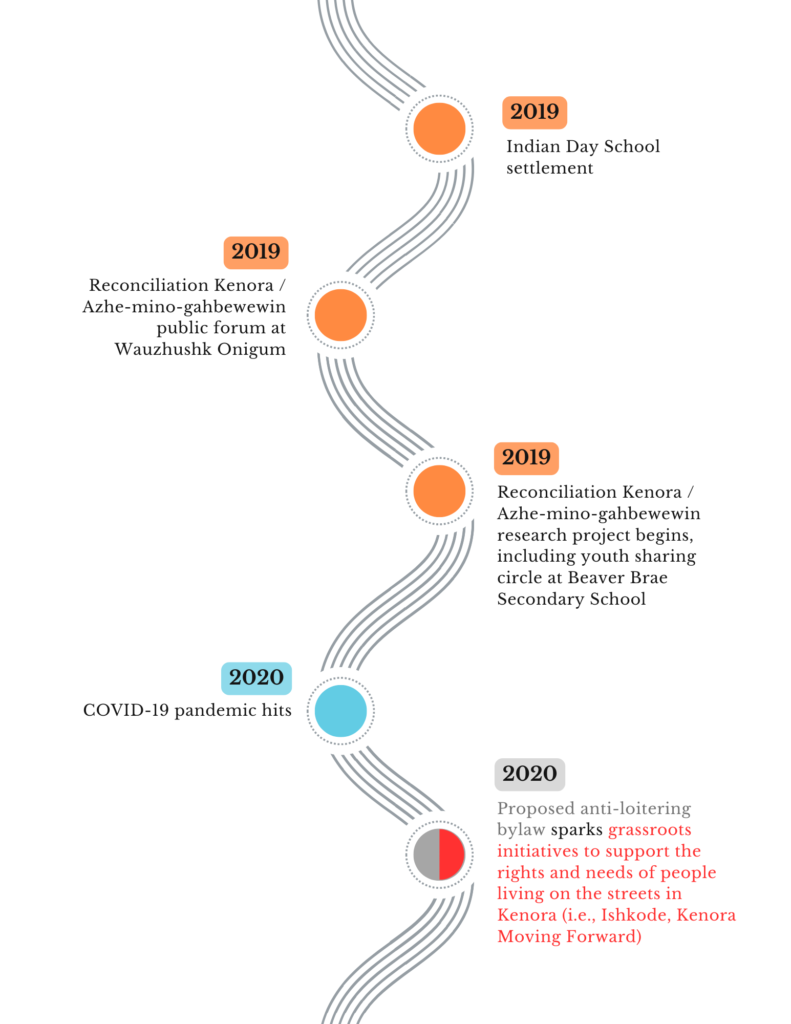

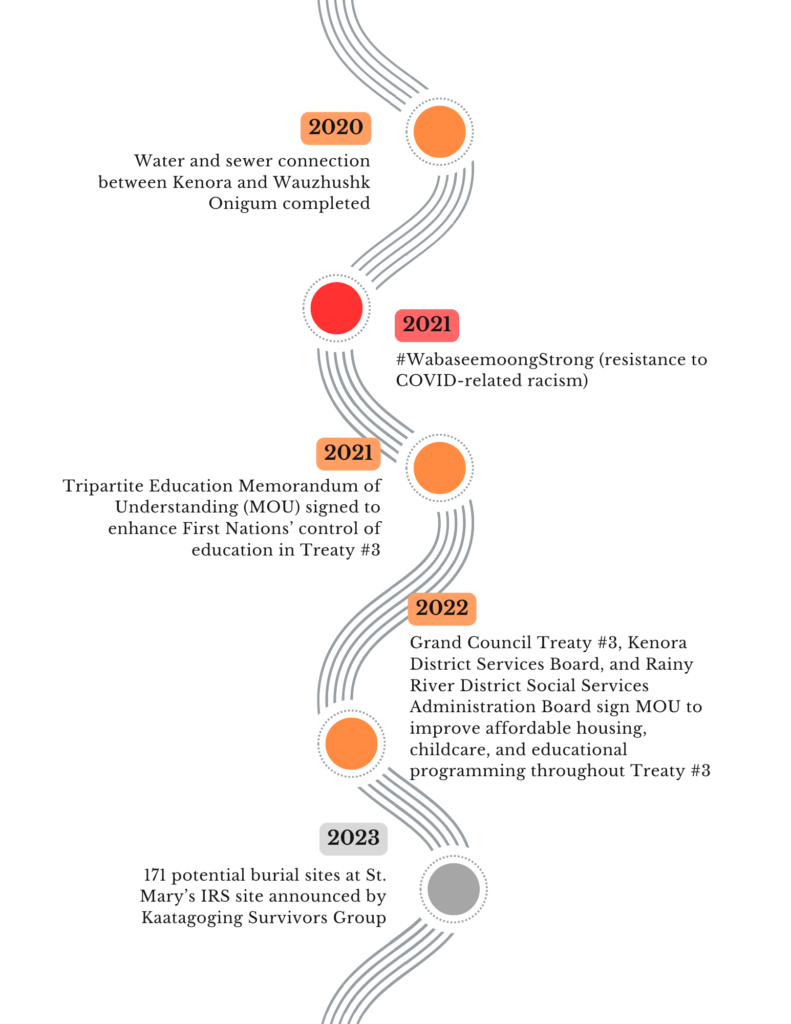

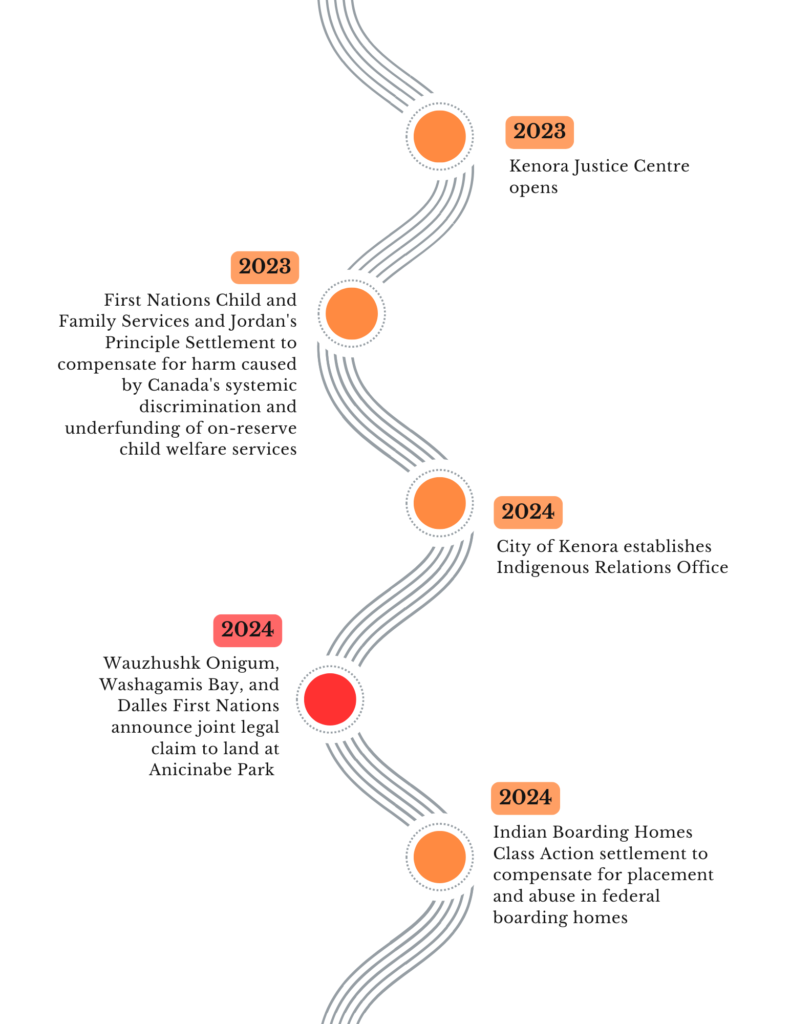

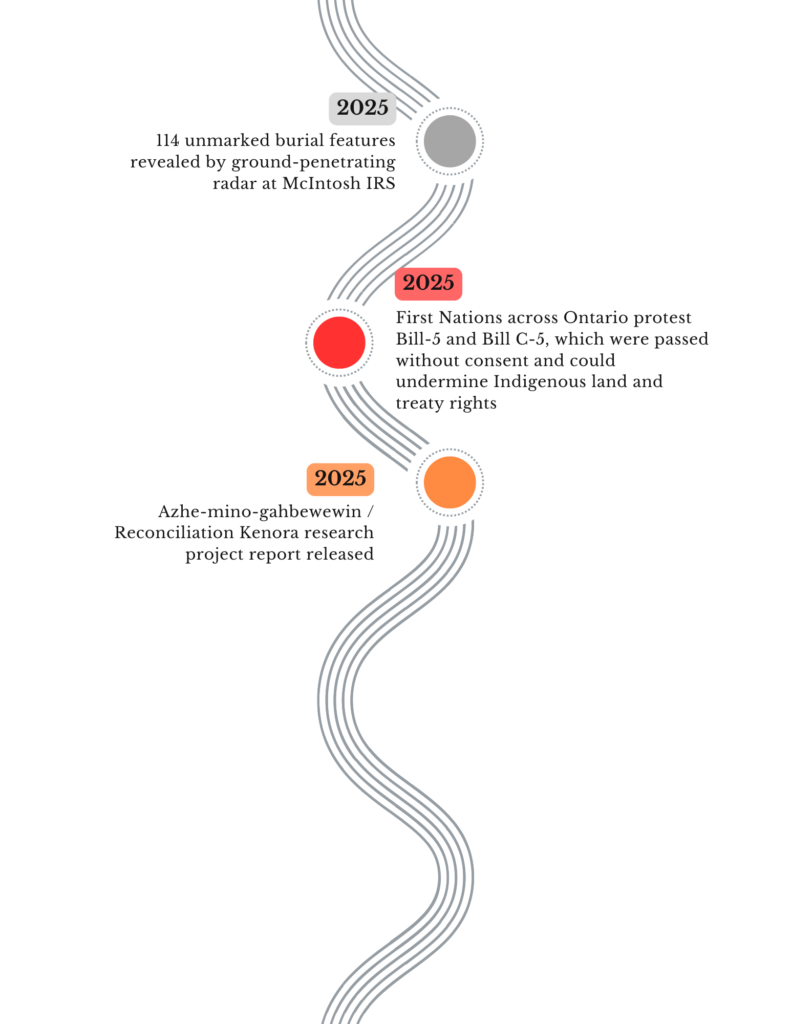

Kenora’s history is rich and complex, marked by colonial oppression, racism, and violence, but also by many efforts to build bridges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. While a comprehensive history of Indigenous-settler relations in the Kenora area is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to highlight some features of the local context that have set in motion distinct kinds of relationships and mindsets, and that continue to shape both the barriers and opportunities for reconciliation today. (For a historical timeline, see Appendix).

Once labelled “Canada’s Alabama” for its rigid racial divide (Anglin, 1965; Clarke, 1965), Kenora—whose current population stands at about 15,000, including 12% First Nations, 11% Métis, and a majority white/European-descended residents (Statistics Canada, 2022)—has a longstanding reputation for racism, violence, poverty, and houselessness (Malone, 2018). It has also been a hotbed of Indigenous rights and reconciliation activism (Kinew, 2015; Rutherford, 2020). The surrounding area is home to 10 First Nations within roughly an hour’s drive, with an on-reserve population of more than 4,000, underscoring the region’s strong Indigenous presence.

The Anishinaabe of this region have long been a powerful independent nation, with their own governance systems, economies, social structures, and vibrant cultural practices (Denis, 2020; Grand Council Treaty #3, 2013, 2023; Luby, 2020; Willow, 2012). After extensive negotiation, the Anishinaabe and the Crown signed Treaty #3 in 1873. While the Anishinaabe viewed the treaty as a peace and friendship agreement between autonomous nations, the Canadian government treated it as a legal “surrender” of 55,000 square miles of land in exchange for much smaller reserves, annuities, and the protection of harvesting rights (Krasowski, 2019; Mainville, 2007).

Soon afterwards, settlers and settler governments violated the treaty. In 1876, the federal government imposed the Indian Act on First Nations, seeking to control virtually every aspect of their lives, including identity (‘Indian’ status), marriage, mobility, and voting rights (Joseph, 2018). Across Treaty #3, reserve lands and wild rice beds were flooded, hunting and fishing restrictions were enforced, gold was mined on the Rat Portage (Wauzhushk Onigum) reserve without consent or compensation, Shoal Lake 40 was cut off from the mainland during construction of the Greater Winnipeg Water District aqueduct, and multiple First Nations were forcibly relocated (e.g., Luby, 2020; Perry, 2016; Waisberg et al., 1996). Such actions were upheld by court decisions, such as St. Catharine’s Milling and Lumber Company vs. The Queen (1888), in which the Anishinaabe were labelled “heathens and barbarians,” “rude red men,” and an “inferior race … in an inferior state of civilization” (quoted in Waisberg et al., 1996: 342). In short, the balance of power shifted decisively (Denis, 2020).

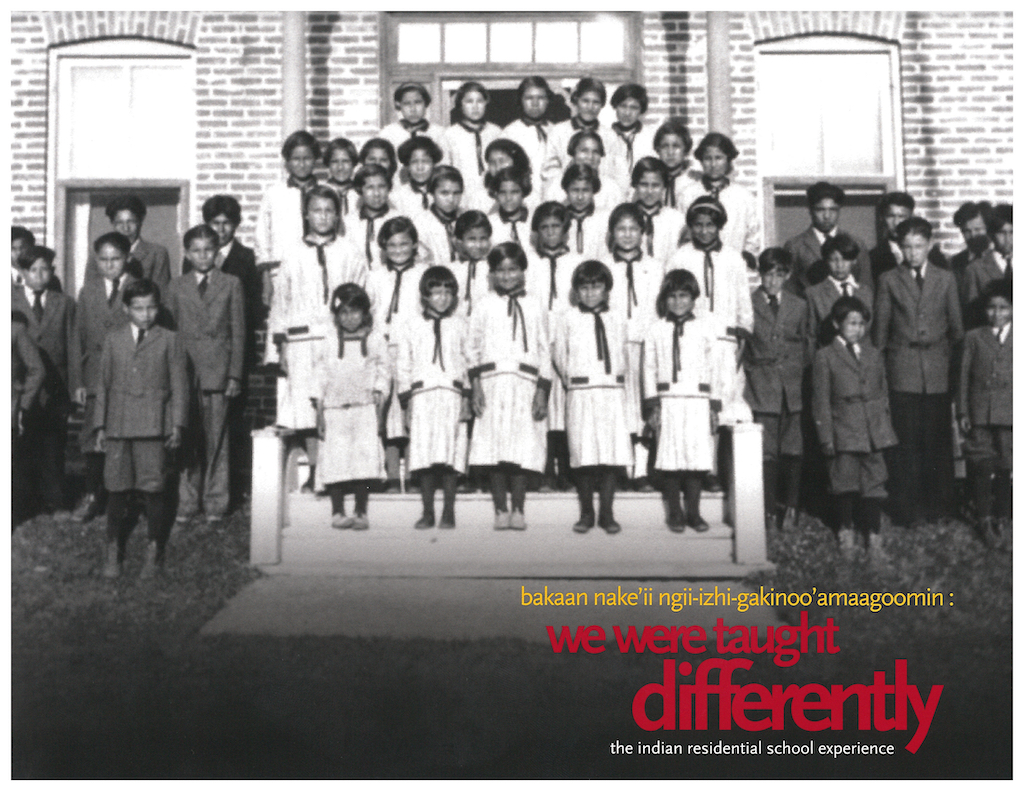

The early 20th century brought further trauma, as the Crown expropriated Indigenous lands and resources, and Indigenous families were torn apart. Treaty #3 had one of the highest concentrations of residential schools in Canada, including three in the vicinity of Kenora—Cecilia Jeffrey (1902-1976), McIntosh (1925-1969), and St. Mary’s (1897-1972)—where multiple generations of Anishinaabe and Métis children were abused, neglected, and, in some cases, died (TRC, 2015).

Story Box 1: Name Change

Adolphus Cameron: “When I was seven, I went to residential school. It took me a while to learn English, but my friends that I grew up with around Minaki, they helped me get adjusted. Well, they told me the do’s and don’ts of being around there. I always had long hair and when I got into residential school, you got it shaved off; now, you’re a brush cut. And it was my relatives at Cecilia Jeffrey [CJ] that used to tell me what I was being asked and how I was supposed to do things. But they’d whisper to me in Ojibway because they didn’t want to get into trouble. We weren’t allowed to speak openly in our language. My parents tried to prepare me, and they helped me write my name, which they told me at the time was Douglas Cameron. But according to the band registry, I was registered as Adolphus Hunter. So, when I went to school, some of us were asked to write our names on a blackboard. And we had one of the famous teachers of CJ. [She was] the first teacher I ever had. So, when I wrote Douglas Cameron on the blackboard, she made sure I forgot about that. She slapped her students! And I got slapped a few times, until I got used to the name Adolphus Hunter. [Pause] So, … for me to get away from any type of corporal punishment, I had to learn fast. Learn English. Learn to spell. I also learned not to speak in my language …. As a kid, I thought everything they were trying to teach me was really the best way, so I tried to fit in … I had seen the difference in the way Anishinaabe people were being treated at an early age and I didn’t want to be treated like that. But no matter if I had the best marks in school, if I did things great, it was still the same: nothing changed.”

Meanwhile, white settlers controlled Kenora’s political institutions and monopolized the well-paid jobs in forestry, mining, tourism, and social services (Rutherford, 2020). While some settlers also faced hardship, many benefited—directly or indirectly—from the exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources, and their comfort, wealth, and security often came at Indigenous Peoples’ expense. Indigenous families, by contrast, were coping with the intergenerational impacts of colonial violence, systemic exclusion, and harsh living conditions.

Yet, Anishinaabe and Métis people survived and resisted. In fact, Kenora became an epicentre of Indigenous activism. Amid the extreme inequality, in 1965, more than 400 members of nearby First Nations bussed into downtown Kenora and marched peacefully to protest racism and poverty—an event that came to be known as “Canada’s first civil rights march” (Rutherford, 2020). At that time:

“… on average one indigenous person a week was found dead somewhere on a Kenora street. There was open, random violence against indigenous people [and] indigenous people weren’t allowed in the same restaurants or bars non-indigenous people frequented.” (Paul, 2015: np)

Figure 2: Winnipeg Free Press headline re: Kenora civil rights march, 1965. [Creative Commons]

After securing a meeting with the mayor and capturing media attention, some small and largely symbolic steps were taken, such as the creation of a race relations committee in Kenora. However, racism and poverty persisted, land and resources continued to be appropriated, and Treaty #3 was still being violated.

In 1973, the Concerned Citizens Committee—a subcommittee of the Kenora Social Planning Committee, which included Indigenous and non-Indigenous representatives of various organizations, social services, and government agencies—published the “Violent Deaths Report” (also known as “While People Sleep”). It highlighted the high rate of sudden, “unnatural” deaths among Indigenous people in Kenora (Rutherford, 2020: 87) and recommended more funding for social services, housing, mobile clinics, a detox centre, better police training, recreational facilities on reserve, increased Indigenous participation and control, respect for Indigenous culture, and “major educational efforts to improve white attitudes toward native people” (Concerned Citizens Committee, 1973: 21-22). That fall, the Ojibwa Warriors Society (OWS), led by Louis Cameron (Wabaseemoong), staged a 36-hour sit-in at the Department of Indian Affairs office, calling for “greater economic autonomy for local First Nations, government action on mercury contamination, and an end to the physical brutality, discrimination, and racism they experienced in Kenora” (Rutherford, 2020: 103).

In 1974, with these issues unresolved, the OWS organized a 39-day armed occupation of Anicinabe Park to draw attention to the land question, ongoing colonial violence, and Indigenous Peoples’ dire socioeconomic conditions (Dunk, 2003). They asserted that the federal government had sold the 14-acre park to the City of Kenora without the First Nations’ consent, and called for better housing, education, and health care, and an end to police brutality. In response, a Kenora nurse published the pamphlet Bended Elbow, which blamed Indigenous Peoples’ social problems on their own “irresponsible” behaviour and claimed that white taxpayers were the true victims of “discrimination” (Jacobsen, 1975). The Kenora mayor blamed the federal and provincial governments, and said he hoped the demonstration would lead to positive change for Indigenous Peoples. Eventually, the Ontario premier agreed to meet with Grand Council Treaty #3 to develop a framework for discussions around land disputes, harvesting rights, and conservation. The OWS ended the occupation when weapons charges were dropped, settler governments said they would study the OWS recommendations, and Grand Council Treaty #3 said it would file a land claim for Anicinabe Park (Rutherford, 2020).

Figure 3: Ojibway Warriors Society (Louis Cameron in the centre) at Anicinabe Park, 1974. [Photo by Canadian Press, reproduced in Harper (1979: 8)]

Yet, racial tensions and inequities persisted. A white gang known as the Kenora Indian Beaters targeted Indigenous residents, especially those living on the streets (Jackson, 2021). Nearby, the Grassy Narrows (Asubpeeschoseewagong) and Whitedog (Wabaseemoong) First Nations suffered the effects of mercury poisoning linked to illegal dumping by a paper mill in Dryden (Willow, 2012). In 2002, Grassy Narrows women and youth initiated what became the longest running anti-logging blockade in Canada to protect their lands from clear-cutting and demand mercury justice (Turner, 2023). Meanwhile, hundreds of Indigenous children across Treaty #3 were forcibly removed from their families and adopted out to white households through the Sixties Scoop and Millennium Scoop (Smith, 2013; Vowel, 2016). By the early 2000s, 94% of Indigenous residents in Kenora reported personal experiences of racial discrimination (Urban Aboriginal Task Force, 2007), and tensions escalated after the killing of Anishinaabe man Max Kakegamic on the city’s streets and a series of lawsuits and investigations into local police misconduct (Makin, 2004).

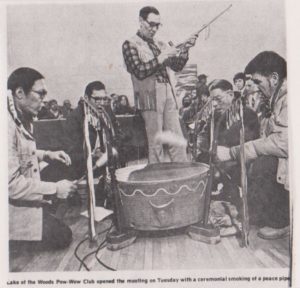

At the same time, Kenora has been a focal point for Anishinaabe cultural revival. The Lake of the Woods Powwow Club, founded in the early 1970s, sought to regenerate traditional knowledge and cultural practices and to support Anishinaabe residents coping with colonial trauma (Smith, 2014). Members self-consciously (re)learned and reclaimed drum songs and teachings, practiced beading, storytelling, and dancing, and organized annual community powwows. More broadly, Treaty #3 is well known for its spiritual strength, longstanding Midewiwin (Grand Medicine Society) practices, and ongoing efforts to revitalize Anishinaabe language and ceremonies.

Figure 4: Lake of the Woods Powwow Club, Kenora, late 1970s. [Photo from Smith (2014)]

In addition, Kenora has seen many efforts toward Indigenous-settler alliance-building and reconciliation. Starting in 1965, an Indian-White Committee (IWC), consisting of local Indigenous and settler residents, including Fred Greene (Shoal Lake 39), Harry Shankowsky (settler), and Fred Kelly (Onigaming), met regularly and sought to educate the public by, for example, hosting guest speakers to talk about “cross-cultural tensions” (Rutherford, 2011: 89). They also wrote reports and lobbied for change in Indigenous living conditions. Together, they organized the 1965 civil rights march, and their speeches framed Indigenous and white residents as “neighbours” who were both responsible for finding solutions to their “mutual problems” (Rutherford, 2011: 49-50).

Meanwhile, Daniel Hill, the Black Canadian chair of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, gathered complaints about the mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples in Kenora and advocated on their behalf. White activists, lawyers, and others supported the Anicinabe Park occupation. Another group, led by Anishinaabe residents Richard Green and Joe Morrison, created the Kenora Street Patrol to ensure safety, food, and shelter for the city’s mainly Indigenous houseless community (Maxwell, 2011). The Ne-Chee Friendship Centre further contributed by organizing “Red and White Socials” that brought together Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents in fun social events.

Bridge-building efforts picked up again in the early 2000s when the Anishinaabeg of Treaty #3 and the City of Kenora entered a unique partnership known as the Common Ground Initiative. This “local process of formal government-to-government relationship-building and negotiation” involves the co-management of Tunnel Island, land formerly owned by the Abitibi Consolidated forestry company and over which the city previously sought unilateral control (Wallace, 2013: 137). Aiming to reconstruct “an equitable treaty partnership,” Common Ground has fostered inter-community group dialogue, centred Anishinaabe ceremonies and worldviews, and drawn on personal and collective stories tied to the land to work towards a common vision for the future (138).

Figure 5: Tunnel Island or Wassay Gaa Bo, site of the Common Ground Initiative, 2024. [Photo by Jeffrey Denis]

More recently, as this report will highlight, local reconciliation—as well as healing and resurgence—efforts have proliferated. Following the TRC’s (2015) final report, a small group of Indigenous and settler residents formed the non-profit Reconciliation Kenora / Azhe-mino-gahbewewin. Calling for local implementation of the TRC Calls to Action, the group elected a board of directors and adopted a mandate “to undertake and support community initiatives in the Kenora/Treaty 3 Region, which promote reconciliation, … improve relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous people, … and promote education and healing” (Reconciliation Kenora, 2017: np). This research project was launched to help inform their work.

Although many Kenora residents may not be aware of this history—as our youth sharing circle, described below, suggests—it nevertheless has shaped today’s relationships, material conditions, and political landscape. This report asks: How do residents—especially Elders, youth, and community leaders—perceive Indigenous-settler relations? What does reconciliation mean to them? What do they see as the main barriers? What actions are they taking to improve relationships, and what further steps do they recommend? The “Findings” section will examine these questions, starting with participants’ descriptions of Indigenous-settler relations and how they have changed (or not) over time.

1

Findings and Analysis

Overview

This section summarizes the major findings from our research. It identifies and analyses key themes in participants’ responses to seven questions:

- How would you describe relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in the Kenora area, and how, if at all, have these relationships changed over time?

- What does the term reconciliation mean to you?

- Who do you think is responsible for reconciliation?

- What are the barriers to reconciliation in the Kenora area?

- What reconciliation initiatives have you been involved in, and which (if any) would you identify as models to build upon?

- What additional actions do you think should be taken to advance reconciliation in the Kenora area?

- What is your hope or vision for the future, especially as it concerns Indigenous-settler relations?

Participants discussed a wide range of ideas, initiatives, and recommendations in response to these questions. While many common themes and areas of agreement emerged, there were also conflicting perspectives. Some frequently mentioned ideas and initiatives (e.g., cultural sensitivity training; safe consumptions sites) were praised by some and critiqued by others. Such divergence is unsurprising given the complexity, emotional weight, and power dynamics surrounding reconciliation.

Indeed, a core challenge, as some participants emphasized, is transforming existing power structures within (and beyond) Treaty #3 without provoking so much backlash that it jeopardizes the entire project. For this reason, they stressed the importance of continuously building respectful relationships, trust, and opportunities for ongoing learning and education. This is the spirit in which the present report has been written.

Describing Indigenous-Settler Relations in Kenora

Story Box 2: Welcome Wagon

Jeanette Skead: “It was around 1970, and we had just moved [to Kenora] from the [Wauzhushk Onigum] reserve. One day, me and my auntie were home with her little baby girl [who] was about 6 months old. My uncle went to work. And that afternoon there was a knock on the door … I opened the door. There was this woman standing there, a white woman, and she was holding a big basket, you know, with flowers sticking out and everything, little goodies on the side. [Chuckles] Well, anyway, she asked us where we were from. My auntie said, ‘we are from here, from Rat Portage,’ you know? It was just, no housing, and my uncle found this house and that’s why we moved into town. And the old lady says, ‘oh, okay, well, it was nice to meet you,’ and rushes off …. She took away the basket. She didn’t leave any flowers [or] goodies behind. Nothing. She left and that was it. So, that was my experience moving into town. That was the welcome wagon woman.”

Participants were asked to describe relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in the Kenora area and if or how these relationships had changed over time. Responses depended on whether participants were born and raised in Kenora or a nearby community, or had moved there later in life, as more than half of the settler interviewees and a few of the Indigenous interviewees did. In other words, participants’ perceptions reflected their reference points and the moment when they became aware of Kenora’s social dynamics.

Even so, virtually all participants agreed that Kenora had a troubled history of Indigenous-settler conflict, racism, inequality, poverty, violence, and colonial trauma. Many regarded Indigenous-settler relations and Indigenous living conditions in Kenora as worse than in other parts of Canada. Many also agreed that the racism and conflict had been more overt in the past, though there was some difference of opinion around how much relationships and conditions have changed over time.

When describing what relationships were like when they were growing up or when they first arrived in Kenora, participants commonly pointed to overt racism and violence against Indigenous Peoples, segregation and exclusion, the visibility of public drinking among a range of residents (including but not limited to Indigenous people living on the streets), the social and mental health effects of IRS trauma, ongoing assimilation pressures, and the strong sense of ‘us vs. them,’ mistrust, and division between Indigenous and settler communities.

Most of the older Anishinaabe interviewees were IRS survivors, and some shared traumatic childhood memories. Some also contrasted their IRS experiences with their family experiences, suggesting that although they may not have been economically rich as children, they were happy and healthy living a more traditional life among their kin. Elder Jeanette Skead recalled:

“All the Anishinaabe families from all over [Treaty #3] would group together for blueberry picking … every summer we were basically like that. Then, in the fall, all the families would move again, out on the lake, and we’d go rice picking …. In those days, families were families. We wouldn’t leave anybody behind.”

Some Anishinaabe also described visiting Kenora for supplies or services, but not being allowed in certain stores or restaurants, and being warned to be cautious around white strangers. As Elder Skead explained:

“[We] mostly travelled by canoe and boat …. It was just my parents that were allowed to go and shop, and come right back, and then we’d head home. [They told me to] stay close to the boat and watch my little brothers [and] be wary of people, especially the white people.”

Many Indigenous participants reflected on experiences with racism, police brutality, and violence in the Kenora area. For example:

“On one occasion, I had symptoms of a heart attack … pain in my chest … short of breath. My lower jaw was hurting …. I came in by ambulance, and then waited for the doctor, and they did tests …. They were all negative …. So, I asked the doctor, ‘why is this happening?’ …. His response was, ‘most Indians that drink a lot will have those symptoms.’ Me and my wife were sitting there, and we both laughed. We don’t drink!” – Grand Chief of Treaty #3, Francis Kavanaugh

“I remember one time we [Anishinaabe] got into a big fight with [some white guys in] Kenora. They had to phone fire trucks on us and the police. They hosed us down. There was a street brawl between, oh, 30, 40 people, right in front of the Lake of the Woods. We were all having a good time, drinking beer. We didn’t know that the [white] people were just waiting for us [outside]. I got knocked down under somebody’s truck …. Somebody hit me, almost knocked me out. And when I came to my senses, all I seen was this muffler, and I heard ‘brrrr!’, and I said, ‘oh, wow, I better get outta here!’” – Tommy Keesick (Anishinaabe)

Some participants, especially those from mixed backgrounds, also discussed racism within their families.

“I remember growing up and experiencing racism …. There’s no other way of putting it …. Even within my own family, there were … very disparaging and rude comments about our First Nation population. I remember looking at family photos and one of my great uncles saying that, you know, we’re not, we don’t have Indian in us. It was ‘Mexican.’ And it’s like, okay, yeah, ‘cause there’s a really big Mexican colony on Lake of the Woods! But because First Nations people were so poorly regarded, [some] people didn’t want to admit they had First Nations ancestry … if they could hide it, they often would.” – Métis participant

Younger Anishinaabe participants who grew up on reserve were sometimes startled when they visited Kenora to see the racialized inequality, including the visibility of Indigenous people living on the streets. They spoke about feeling shame, sadness, anger, and injustice, and about learning early on about colonial trauma.

“I’d travel [to Kenora] a lot for groceries, for doctors and dentist appointments, and just necessities to bring back to the rez …. I remember the adults in my family, they’d tell us to be careful …. I witnessed a lot of racism …. I also saw a lot of homeless people …. [They’d often] lay in the grass by the old Zellers …. And my grandpa used to talk to them [in] Ojibwe. I don’t know what they were saying, [but] I never saw them as people to be scared of.” – Anishinaabe participant

Settler participants who grew up in Kenora echoed many of these themes. Many recalled witnessing racism and exclusion and being concerned about the large number of Indigenous people living on the streets. According to former City Councillor Rory McMillan (non-Indigenous):

“[In the 1960s-70s], people from First Nations would come into town to conduct their business and sometimes they wouldn’t be able to get home, so they’d find a place to stay overnight, whether it was near a dock or wherever. [And] there were stories shared that [white] people were coming along and pushing [First Nations] people off the docks and into the lake and, in some cases, there were deaths. It was a very major concern.”

Many settlers remembered seeing stark inequalities and assuming Indigenous people just “kept to themselves,” but now realized that they lacked the historical and political context to make sense of the situation:

“I think, as a child growing up, there was a lack of knowledge of the history and some of the challenges that exist as a result … I had questions about why things were the way they were, you know, why certain people don’t have access to the same things we do, why their home life is so different, why so few of them graduated from high school. At that point, I couldn’t comprehend why, but I knew there was differences.” – settler participant

Locally born settlers were also more likely to discuss cross-group childhood friendships. Some older white and Métis men recalled playing hockey against First Nations peers and even visiting them at nearby residential schools. According to a non-Indigenous former municipal politician:

“There was an exchange, so kids from CJ [Cecilia Jeffrey IRS] would come to Valleyview [Public School] and we went to CJ. They had one of them neat fire escapes on the third floor, like a water slide you could go down … as a young kid, when I had my birthday parties, kids from CJ would come.”

In retrospect, some settlers also acknowledged their parents’ racist attitudes or their own past problematic views.

“I’m sure, at certain points in my life, I said some very stupid things and things that I regret. And it’s still a challenge for me to sometimes get my head around it. But obviously residential schools, anybody who’s had children, you feel it in your gut when you hear how children were taken away from their parents and everything that happened to them.” – settler participant

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous interviewees who moved to Kenora later in life often compared their experiences unfavourably with other places. Many said they were appalled by the overt racism and racialized poverty that they encountered in Kenora, and their overall sense was that relationships were “tense and bitter.”

“I’d say it was a culture shock because I come from a community where my whole schooling, my whole neighbourhood, was so multicultural, so many different nationalities, and then to come to a town where it’s essentially red and white, that was a shock for me. And a shock at the racism in this town. It was an eye opener. I’d experienced some racism in Winnipeg, but not to the extent when I first moved here.” – Tania Cameron (Anishinaabe)

“My first exposure to Kenora was driving through on my way to Winnipeg … I was with a friend, and we were like, ‘what is going on here?’ There was just something so apparently wrong with this picture … there were street people everywhere … almost all the faces were brown, and that image has stayed with me ever since.” – former Executive Director for Waasegiizhig Nanaandawe’iyewigamig (WNHAC) Anita Cameron (Indigenous)

“When I moved to Kenora, you did not see an Indigenous person working anywhere in town …. And I don’t think it’s because there was a lack of will. I think it was a racial thing. My social world includes some real rednecks who grew up during that time, and there’s no doubt about it, all the stories about, you know, Friday night, the boys go out, they’re gonna beat up an Indian, right? That was definitely happening.” – non-Indigenous participant

Some participants also offered vivid metaphors for the distance between communities:

“It really was two ships in the night. If you went to non-Indigenous events, very few Indigenous people came. If you went to Indigenous events, and it’s still—I can almost name on two hands the number of people who are not Indigenous who go to … powwows, feasts, or whatever.” – Sallie Hunt (settler) [Italics added]

“I moved into town with my mom in grade three, and it was a very different side of the tracks … I didn’t know I was poor until I left the reserve. And then that’s when town told me I was poor and I looked that way and you’re, you know, bullied and [there was] lots of racism.” – Anishinaabe participant [Italics added]

At the same time, long-term residents offered nuanced analyses. Even during the overt racism and violence of the 1970s, including the Anicinabe Park occupation, some said the city wasn’t completely divided and there were always people in both communities trying to build bridges and seek social justice. Many of these participants had cross-group friendships. Many also described how some settlers acted as allies—from Indian-White Committee members to white activists, lawyers, teachers, boarding parents, doctors, and church ministers who supported Indigenous families and causes.

Have Indigenous-Settler Relations in Kenora Improved Over Time?

Overall, most interviewees agreed that Indigenous-settler relationships in the Kenora area have improved in some ways, but opinions varied on how meaningful these changes have been. Some viewed recent shifts as mostly symbolic, while others saw more substantial progress. Reported improvements included:

- Positive changes in the education system, including improved school curricula and more Indigenous students graduating, pursuing postsecondary education, and often returning to their communities to “give back.”

“The curricula are changing. And instead of the condemnation and obliteration of the language and culture, in some schools, the Ojibwe language is being taught. Elders are involved in school programs. And culture is increasingly being recognized and celebrated.” – retired judge E.W. Stach (settler)

- More awareness among settlers. As one Anishinaabe participant said, “the gap in understanding has closed a bit.”

- More cross-group interaction.

“In that 50-year span from when I was in public school to now, … I’ve seen much more interaction between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. I see Indigenous people in workplaces where I don’t recall ever seeing it growing up. And there’s more cultural sharing.” – non-Indigenous participant

Figure 6: Reconciliation Kenora board members Jake Boutwell (settler) and Jeanette Skead (Anishinaabe) working together at Wauzhushk Onigum, ca. 2018. [Photo by Kathleen Skead]

- More Indigenous people working in ‘mainstream’ organizations and broader representation across sectors.

“I’ve seen a lot of improvements …. I’m seeing Indigenous students working in the stores now. You know, that never happened in the past …. People are a bit more open-minded now. So, it’s starting. And I think it’s up to us to continue the work that’s been started by the [Elders].” – Daryl Redsky (Anishinaabe), speaking to the youth sharing circle

- The growth of Indigenous organizations, some with substantial resources (though some Indigenous participants also raised concerns about corruption and growing inequality within Indigenous communities).

“[Indigenous] people are certainly allowed in restaurants and stores now …. There are so many more Anishinaabe people working in town …. And like in other communities in the region, Indigenous organizations have grown from basically none in the late 1960s to dozens today …. I’d say at least 1,000 people here work directly for Indigenous organizations.” – Mary Alice Smith (settler/Omashkiigoo-James Bay Cree)

- More collaboration and partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous organizations in health care, social services, and beyond.

“There seems to be a bit more cooperation than before. You know, if you look around not only at the reserve communities, but at the towns of Kenora, Dryden, Fort Frances, … there is a lot of commonalities in the issues we’re facing. So, I’ve had several meetings with mayors and reeves across Northwestern Ontario … about how we’re going to deal with these problems, you know, housing, mental health, the drug issues … and we’ve begun to create partnerships.” – Grand Chief of Treaty #3, Francis Kavanaugh

- Greater visibility and celebration of Indigenous cultures, languages, and identities.

“I think for young people and those with perhaps a more progressive mindset, the relationship is probably a lot better … and some of that has to do with the involvement with powwows and Indigenous Day and [other] big, exciting Indigenous events that have been put on.” – Dr. Jonny Grek (settler)

- Less overt racism, public intoxication, and violence—and less tolerance for such behaviour.

“Compared to when I first arrived in Kenora [30+ years ago], there didn’t seem to be nearly as many people on the street [and] public drunkenness seemed to have subsided …. The conversation and the situation with racism seemed to be improving. But I now wonder if it just became less socially acceptable to be overtly racist. Like how much of it is just sort of outward behaviour?” – Indigenous participant

Figure 7: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Memorial in Kenora, 2023. [Photo by Jeffrey Denis]

Indeed, despite these positive steps, many participants stressed that longstanding inequalities and conflicts remain, and some believed that nothing has fundamentally changed. In describing current Indigenous-settler relations, participants noted:

- A persistent divide between ‘us and them,’ along with polarized views on many social issues.

“I think I’m fortunate to straddle worlds, because I have my redneck world and my politically correct world, and … the rednecks just won’t go to [Indigenous] events, or they’ll say nothing if they find themselves there because of the animosity between the two groups …. There’s also a huge resentment about the businesses downtown being bought up by Indigenous agencies. [And] the longstanding [white] Kenora citizens say they’re afraid to go downtown now, which I think they’re exaggerating.” – non-Indigenous participant

- A deeply entrenched power imbalance, despite recent gains by Indigenous communities.

“I think the biggest challenge in this whole reconciliation conversation [is] that there’s a power dynamic in this town …. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered anything quite like it, but where a certain portion of the community has the power, the privilege, and it is just so deeply ingrained. It’s so taken for granted that the concept of things being any other way is just unfathomable.” – Anita Cameron (Indigenous)

- An ongoing houselessness and mental health crisis, which disproportionately affects Indigenous Peoples due to colonial trauma (Bombay, Matheson, & Anisman, 2014), and which, if anything, worsened in recent years.

“As I grew up, I felt like there was more and more houseless Indigenous people in Kenora. And they were young, like my age or younger. And I was like, ‘what the hell is going on?’ … [During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kenora Moving Forward] opened warming spaces at the churches, and I helped with that. I even stayed there alongside another woman, and I got to see like all the houseless community in there … and I noticed a lot of them have mental health issues.” – younger Anishinaabe participant

- Unresolved conflicts around land and treaties, including ongoing land claims and concerns about treaty violations.

“I think a good show on the part of the settler community [would be] to give this land back. If not those particular chunks, at least an equal amount somewhere, because they’re always taking land. They always have.” – Anishinaabe participant

- Continued exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources, despite Grand Council Treaty #3’s Manito Aki Inakonigaawin (Great Earth Law).

“Nothing has changed. We’re nothing but a dollar sign to a lot of people.” – Kelvin Boucher-Chicago (Anishinaabe), Treaty #3 Grassroots Citizens Coalition

Figure 8: A clear-cut section of the Whiskey Jack Forest, Grassy Narrows, 2006. [Photo from freegrassy.net]

- Frequent clashes over control of services and decision-making authority, including whose laws—Indigenous or settler state—should take precedence.

“The whole intent was to create a safety net for the street people in Kenora. [But due to] politics or posturing or whatever you want to call it, control, that didn’t work out. [Another organization took over and] they’re more of a western mindset, even though a whole bunch of Indians work there.” – Anishinaabe participant describing how a grassroots initiative to support houseless people was co-opted by a Western-style organization

- Continued incidents of racism and violence. For example, several participants discussed an incident in 2022 when a houseless Indigenous man with mental health issues entered the downtown store, Island Girl, and allegedly assaulted the owner (though the owner’s video shows the man on the floor and her holding a hammer). In response, hateful comments were posted online, including at least one calling for “vigilante justice.” In an apparent reference to the Starlight Tours (Green, 2006), a white resident wrote, “Kenora police, when we had them, would drive people like this to the edge of the town and would leave them there. Why can’t we do that?” (cited in Fleury, 2023). In my interviews, Anishinaabe Elders confirmed that this had happened in Kenora’s past. The online comments were condemned by Indigenous and non-Indigenous activists, and Kenora city council held a special public meeting, which led to the promise of a new Community Safety and Well-Being Plan.

“It’s sad that such terrible views are still held in this community. And I think some people just don’t get how dangerous it is for the vulnerable in this town …. You’re not allowed to call for violence on a segment of people …. We have to call out racism. [And] we have to look at the vulnerable as humans [who] need proper care, mental health services, and access to safe, affordable housing.” – Tania Cameron (Anishinaabe)

- Concerns about tokenism, even as more Indigenous people are working in town and serving on boards.

“I’m welcome to be a part of the larger community as a token, [and] that is a very uncomfortable place to be after a while. When you get all your personal issues sorted out and you don’t need that kind of ego stroking anymore, you just feel used.” – Indigenous participant not originally from Kenora

- A growing backlash among some settlers, who feel threatened by decolonial movements and recent changes that have benefited Indigenous Peoples.

“I know there’s always been divides, but sometimes it feels like the divide is becoming more intense. Especially after those recent incidents with the street community, a lot of [non-Indigenous] people seem threatened and scared.” – Elauna Boutwell (settler participant)

“My children who are now raising their children in Kenora are, I would say, shockingly racist. And it didn’t come from me …. It may have come from a culture that felt the pendulum had swung too far, and now [white people] weren’t being treated fairly.” – settler participant

- Many initiatives seem to ‘preach to the converted.’ Although a strong core of Indigenous and non-Indigenous activists works well together, many participants believed there is still widespread ignorance and fear among settlers and limited interaction between the communities overall.

Story Box 3: Bystander Effect

Mary Alice Smith: “The racism and stereotypes are so ingrained here. Sometimes it seems that things haven’t changed much over the years. My late mother-in-law Ada Morrison shared a vivid memory of an experience in downtown Kenora back in the ‘70s when she was working at the courthouse. She’d had severe rheumatoid arthritis since her late teens. With a knee and ankle fused, she always walked with a cane and was in constant pain. One day she was crossing a busy intersection by the chip truck, in the middle of the day, when her leg gave out and she fell to the pavement. Unable to get up on her own, she just laid there; people walked by and around her. Nobody looked down at her or asked if she was okay. She said she lay there for a long time until finally someone who knew her came by. ‘Oh, Ada! Are you okay?’ They helped her up and to the other side of the street. I often imagine what that must have been like to be lying there and having people walk around you, like you didn’t even exist … ‘oh, there’s another drunk Indian lying on the street, how disgusting, how sad.’ You might think, ‘oh, but that was 50 years ago.’ Yet just last winter [2020] the same thing happened to our family’s auntie Dorothy. She was walking down Matheson Street by the laundromat, in the winter. It was icy. She fell and broke her hip, couldn’t move. She was in a lot of pain, moaning. And people just kept walking by. Again, another Anishinaabe person who knew her was driving by, and they pulled over right away and got her to the hospital. But it’s the unresponsive bystander phenomenon where people usually don’t stop to help if someone is different from them; you don’t think of them as part of your community. It’s like the brain is wired to say, ‘they’re not one of us, ignore them, it’s not my problem.’ But if it’s someone like us, our empathy kicks in.”

Given these perceptions of past and present relationships, the next section will examine what ‘reconciliation’ means to Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants today.

What Reconciliation Means

All participants were asked what the term reconciliation means to them. Not surprisingly, they shared a wide range of perspectives, which tended to fall into three broad categories.

- A process of learning, healing, and building better relationships.

Many participants echoed the TRC (2015), defining reconciliation as a combination of learning about the historical and ongoing mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples, healing from past traumas, and working toward more equitable and respectful relationships.

- A preference for the Anishinaabemowin term, Azhe-mino-gahbewewin.

Some participants favoured the name gifted to Reconciliation Kenora by the late Elder Clifford Skead. As he explained at the 2018 AGM, Azhe-mino-gahbewewin means “stepping back to go forward in a good way.” He also said it was about “returning to a place of good standing,” as envisioned by Anishinaabe leaders when Treaty #3 was negotiated in 1873. Because it is locally rooted and expressed in the Anishinaabe language, several participants felt it was more relevant than the generic English term ‘reconciliation.’

- A rejection of reconciliation as a concept.

Others, especially Indigenous participants, argued that reconciliation is a misplaced goal because Indigenous and non-Indigenous people never had good or equitable relationships in Treaty #3 to begin with, at least on a nation-to-nation level. In principle, they said, there may be nothing to reconcile. Several Anishinaabe Elders and leaders stressed that revitalizing Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of being should take priority, rather than seeking reconciliation with settlers who may not be ready or willing to pursue it.

To elaborate on this range of views, the following ideas were each mentioned by three or more participants in response to the question, “What does reconciliation mean to you?”:

- Rebuilding relationships—between and within groups

- Working together to address social issues (e.g., houselessness, addictions)

- Creating spaces where everyone feels welcome

- Treating one another well in everyday interactions

- Listening to and learning from Indigenous Peoples

- Education—especially for settlers; learning about the past to understand present dynamics and avoid repeating harms

- A personal learning and healing journey: reconciling with self and family; for Indigenous Peoples, understanding and healing from the impacts of colonization; for settlers, looking in the mirror and questioning one’s assumptions and biases

- Honouring treaties

- Restoring balance—within oneself (i.e., mental, emotional, physical, spiritual) and between groups (i.e., balance of power)

- Revitalizing Indigenous languages, cultures, and traditions

- Making things right—rectifying inequalities and injustices (e.g., funding gaps, boil-water advisories) and promoting fairness, equity, and inclusion

- Implementing the TRC Calls to Action

- Addressing and eliminating racism

- Breaking down organizational silos and developing partnerships

- Peace and friendship

- Mutual understanding and respect

Many participants emphasized that reconciliation cannot be achieved by a single event or individual. It is an ongoing process involving many people and multiple generations. Some added that truth-telling must come first, and that reconciliation requires concrete action, not just symbolic gestures. Several participants, especially Anishinaabe Elders, also stressed that reconciliation is not only about relationships between or within peoples, but also about relationships with the land. Some connected this idea to the fact that Canada was founded on Indigenous dispossession and argued that any meaningful reconciliation must involve the return of land and governing authority to Indigenous Peoples.

In Participants’ Own Words

- “To me, reconciliation is about bringing back what was, in a lot of cases, taken away from Indigenous people. It’s about educating people … understanding what the treaty’s all about, … understanding the 94 Calls to Action [and] that those things need to happen.” – Martin Camire (Métis)

- “Reconciliation means trying to restore us to a respectful partnership in the sense that was intended by the First Nations at the time of treaty-making.” – E.W. Stach (settler)

- “To have reconciliation, you have to get rid of the racism …. If there’s no common understanding, and if there’s always going to be the settlers up here [gestures high] and the native person down here [gestures low], then reconciliation won’t happen.” – Bepgogoti (Kaiapo)

- “To me, reconciliation is the day-to-day stuff. It’s not an event …. It’s walking down the street or having coffee. Pre-COVID, every Sunday, I used to sit down and have breakfast with a couple of non-Indigenous friends, and we’d talk about different things—things that are comfortable and things that are not so comfortable. That’s the process of reconciliation.” – Adolphus Cameron (Anishinaabe)

- “I think the [term] Azhe-mino-gahbewewin is more helpful. And my understanding of that is sort of like restoring the good life … it’s about journeying towards the good life together.” – Meg Illman-White (settler)

- “That word ‘reconcile’ doesn’t really sit well with me because we were never on good terms anyway. If there wasn’t a good relationship in the beginning, there’s nothing to reconcile, nothing to go back to.” – Kathleen Skead (Anishinaabe)

- “I have nothing to reconcile with the settlers. I do have a lot to reconcile with myself and my family and my community as a result of what happened. The tragedy that I have lived through. The consequences of my actions because of the generational trauma.” – Daryl Redsky (Anishinaabe)

- “It has to be about action. What are we gonna do to make this [relationship] right, to better ourselves, to educate our friends? … Reconciliation is a slow road, but reconcili-action is the shortcut.” – Craig Lavand (Wauzhushk Onigum)

Youth Sharing Circle – Recognition Matters

In the youth sharing circle, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants expressed general support for reconciliation. Although they had a positive impression of the term and perceived it as an important goal, many were unsure how to define it. One student even asked Dr. Denis to explain what the TRC meant by reconciliation.

Still, the youth demonstrated clear, implicit understandings of reconciliation through discussion of activities they had been involved in, such as participation in a First Nations youth council, a local cadets program seeking to involve Indigenous youth, and Orange Shirt Day events at school. These initiatives, they said, helped bring people together and raise awareness about the conditions facing Indigenous Peoples. As one settler student put it:

“I think how to engage people in the process of reconciliation is just doing more things together …. By working together, we can talk to teach other and make more connections. And by doing that, we can learn more and … people will understand.”

Youth were also asked to think of something—an object, person, group, or activity—that symbolizes reconciliation. Their insightful responses included a mixed-heritage family (First Nations father, white mother), a memory of a man from the Netherlands who danced at a local powwow and spoke fluent Anishinaabemowin, and Indigenous artwork and street signs in Anishinaabemowin around Kenora.

Furthermore, reconciliation was exemplified by some of the young people’s actions during the sharing circle itself. Early on, a young Anishinaabe woman said she attended Beaver Brae, but also had a son; as a teenage mother, she had to follow an unconventional educational path. She explained:

“For me to reconcile with people, it’s for people to see who I am. Mostly [people will say], ‘oh, well, you’re not going to graduate high school.’ But here I am. I am graduating. So, it’s just me trying to prove myself [and show] people that we can live together, as human beings.”

After a pause, a young Métis woman responded: “I totally get what you mean …. You’re trying to break the stigma that you can’t finish high school because you decided to have a kid.” She said reconciliation was about combating stereotypes and stigma.

The Anishinaabe co-facilitator Daryl Redsky then praised these young people, saying:

“This is exactly how reconciliation should work—understanding each other …. Just by these two individuals that have engaged, it tells me we’re on our way. You know, [the first student] shared something about herself, and you [the second student] responded in a positive, understanding, and supportive way. To me, that’s reconciliation work.”

This interaction illustrates an important point. Despite academic criticisms of recognition politics (the idea that justice can be achieved simply by being recognized by others), there is value, at the interpersonal level, in being seen as one wishes to be seen, in breaking stereotypes and acknowledging one another’s humanity (cf. Green, 2019). Recognition alone will not undo the unequal power relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, but it is a minimal and necessary starting point for reconciliation—or something like it—to occur.

Responsibility for Reconciliation

When asked “who is responsible for reconciliation?” slightly more than half of all participants said it is everyone’s responsibility. However, many also specified different roles for different groups. Several grounded this view in the idea that, as residents of Treaty #3, “we are all treaty people” with rights and responsibilities that vary depending on one’s Anishinaabe or non-Anishinaabe identity. As Ed Mandamin (Anishinaabe) put it, “we all have a responsibility to research our past in order to see where we want to go in the future … and we’re all binded by the treaty, whether you like it or not.”

Many participants said a key role for settlers is to educate themselves on first principles: learning about the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization, questioning their assumptions, and reflecting on how their own (in)actions and ways of life may support or impede reconciliation. Settlers, they noted, can also support Indigenous-led reconciliation and decolonization initiatives—financially or otherwise—and call on their governments to implement the TRC Calls to Action.

Meanwhile, participants said, Indigenous Peoples’ roles may include being open to sharing their truths and giving settlers a chance to learn and develop more equitable relationships. However, they also stressed that this would take time, and that different people are at different stages in their healing journeys—a process that must be respected. As a young woman of mixed descent in the youth circle explained:

“Healing is really hard, especially for residential [school] survivors. There’s a lot of healing that needs to happen [and] it’s a very long process …. They are still hurting. And I think we have to accept that they have to heal before we can have reconciliation for everybody.”

Further, some participants noted that although many Indigenous people are very generous with their time and willing to educate settlers and include them in events, it is unfair to expect them to always be the teachers. Many said Indigenous communities have been doing most of the heavy lifting on reconciliation and it is beyond time for settlers to step up.

Indeed, many interviewees argued that the primary onus rests with settlers who have benefited from colonization. Some stressed the role of ordinary settlers, at the grassroots level, and the need for reconciliation to be locally driven and part of everyday life. Others put more emphasis on governments, churches, and corporations that imposed colonial policies, operated residential schools, and profited from the theft of Indigenous lands and resources. While ordinary settlers also hold responsibilities, some participants noted that they may not have been fully informed about colonialism and/or may lack the power to directly change harmful laws, policies, and institutions.

Several participants also raised concerns about avoidance or passing the buck—a pattern that must be stopped by taking action when and where one can. Anita Cameron (Indigenous), the former Executive Director of WNHAC, expressed frustration at the “duck and dive exercise” when it comes to implementing the TRC Calls to Action:

“[Governments] just constantly say, ‘that’s not our mandate.’ And if it wasn’t the ‘it’s not a municipal responsibility thing,’ then it would be ‘it’s council—no, it’s administration—no, it’s council—no, it’s administration.’ Or [the province] will say it’s a federal responsibility, and the feds will blame the province.”

In Participants’ Own Words

- “We’ve always been taught that everyone has a role and a responsibility. No one is better or less than anybody, and everyone can contribute to what we now call reconciliation. But it’s really about having healthy relationships …. And I think before we get there, we have to heal together.” – Elder Sherry Copenace (Anishinaabe)

- “It can’t just be political leaders, Chiefs, and prime ministers saying, ‘we need reconciliation’ …. It has to be through bringing everyone, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to a place of mutual understanding.” – local settler politician

- “I think it’s a responsibility of all of us. When you’re in a relationship, you both need to be working at it, and if there’s been a rift, both need to be seeking reconciliation. If only one party is interested, it’s not likely to happen.” – non-Indigenous participant

- “First of all, [settlers] have to educate themselves. They’re the ones that have to take responsibility for reconciliation, not the Indian. We didn’t do anything wrong.” – Anishinaabe participant